As we integrate into living, working farm communities, it’s important to remember that a permaculture farm is not a new idea.

by Marit Parker

It seems to have become popular recently to use the label “permaculture farm.”

I’m a farmer, and I’m also a permaculture practitioner, but I don’t call my farm a permaculture farm. There are a number of reasons why I don’t follow this trend.

First and foremost, permaculture doesn’t teach you how to farm.

Permaculture can teach you how to look at things from different angles and see different perspectives, but it doesn’t teach you how to deal with footrot or liver fluke, or how to lamb. It doesn’t teach you how to lay hedges, repair dry stone walls or put up a fence. I learnt how to farm, and am still learning how to farm, because neighbours and friends have been generous in sharing their knowledge and skills. All sorts of different people have helped and advised me over the years, including women and men who are farmers, smallholders, foresters, engineers, local history experts, vets, cooks, cider-makers, geologists, soil ecologists, conservationists, spinners and weavers…the list goes on and on.

Labelling farms as “permaculture farms” seems to me to be an attempt to set them apart. It’s not the same as calling a farm a “dairy farm” or an “arable farm,” or even an “organic farm.”

The implication seems to be that a “permaculture farm” is superior in some way, which in turn implies criticism of neighbouring farms. Is this perhaps a result of the poor image of farming in media? That people new to farming don’t want to be tarred with the same brush? If so, it demonstrates a lack of understanding that there are many different types of farms and farming, and in particular a lack of understanding that smallholdings, small farms, family farms and hill farms are all very different from large arable farms and from intensive farms.

The second reason I don’t call my farm a permaculture farm is because I can’t help noticing that, with a few exceptions, the label is often aspirational; there’s often not much to see on the ground, and often the people involved haven’t yet built up a wealth of experience.

Farming is a long game. It takes many years to get to know your patch of land. Eventually, you’ll know it like the back of your hand, but initially there are probably neighbours who know it better than you do, who remember where springs have appeared after heavy rain, who know which field is better for lambing and calving. And, when you’re first starting out, those neighbors will be your most valuable resource. Alienating them in the first year by trying to set your farm above theirs, based on ideology rather than action, isn’t wise. And it isn’t sustainable.

It also takes years to build up your reputation, because it takes years to develop a healthy flock or herd, to select healthy seed, to build up fertile soil, to grow or restore hedges, to grow orchards. Farmers gain respect (or not) from others seeing their healthy animals, crops and fields, year in, year out.

In rural areas, people depend on each other much more than in urban areas. Being a good neighbour and having good neighbours, being part of the local community, these all make a big difference to your well-being and to your resilience. Being on hand and offering practical help when there’s a local event, or when a neighbour has an accident or is taken ill, these are all a crucial part of being part of a rural community. Finding shared values and common ground is far more important than setting flags in the ground and highlighting differences. However good your permaculture design, being snowed in still means going out to check, and save, livestock.

And, if you consider the second and third ethics, all of the above considerations are permaculture. And they should be just as important to your design as where to put the pond.

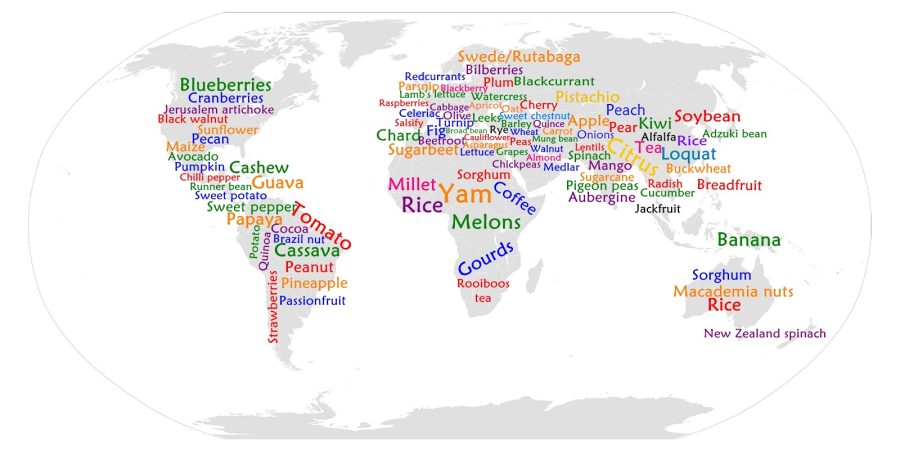

As we integrate into living, working farm communities, it is crucial to remember that permaculture is not a new idea.

It’s a collection of traditional and Indigenous knowledge, from across the world, that has, in many cases, been repackaged for an urban generation that has become disconnected from nature and from each other. Because it is from rural people that the knowledge has been gathered, this means that it is part of the shared common knowledge of rural people. Yes, even in industrialised nations, and yes, still today.

Those of us who grew up in rural areas often grew up with a close connection to our habitat, our square mile, because we need to understand how the natural world works and how we fit in it so that we can thrive in our local landscape. This means that permaculture may not have much to add to the land-based skills of those already immersed in land management. Unless you incorporate the social stuff into your design. Then, permaculture becomes a powerful tool for deeply connecting you to the community in which you live.

Although permaculture is often thought of as being about gardening and farming, it actually applies to any aspect of life.

The three ethics underlying permaculture(earth care, people care and fair shares, plus a recently suggested additional one: future care) mean it is deeply relevant to social issues and to social justice. In rural areas, we face similar problems to urban areas, including homelessness and gentrification, but the problems are often hidden and so get ignored.

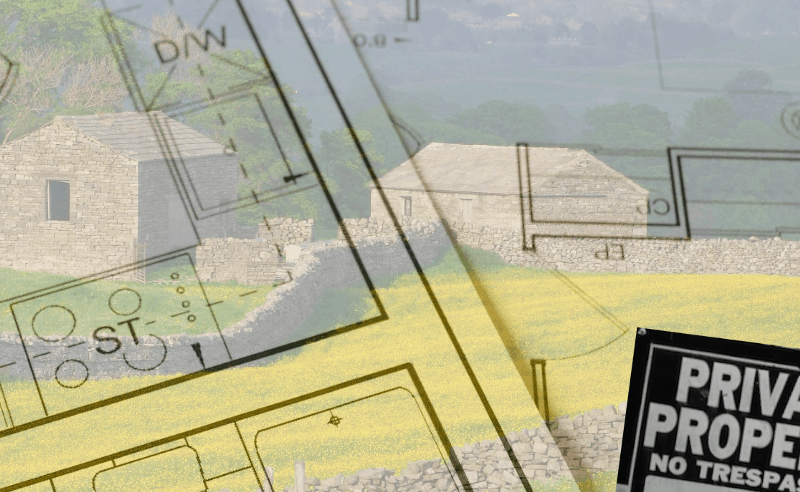

Pressure on land is also an issue, but instead of being for office blocks or luxury flats, it can be for resource extraction (eg mining, quarrying, forestry plantations, dams for water, wind farms), for investment, for a nice place to retire to and lately, for rewilding. Few realise how fragile rural communities are, and how seemingly small changes can result in loss of resilience, loss of knowledge, loss of key people from the community. Language, dialect and culture hold within them generations of knowledge about how to thrive in often harsh landscapes. When young people move away, the thread is broken and can be hard to repair, and especially if incomers see only a blank canvas.

No land is a “blank canvas.”

There is a tendency for those who have completed permaculture courses to think they now need to move to the countryside and buy some land. Sometimes doing this is great and good things happen. But not always. Sometimes however good our intentions, our actions can have negative impacts. It’s important to be aware of the privileges being able to move freely and buy land entail, and also to be aware of the differences in power and privilege of your chosen location.

Taking all three ethics seriously means asking ourselves some uncomfortable questions:

As an incomer, are you a settler? A new colonialist?

Could your arrival have a negative impact on a minority culture or language?

Although the land may be cheap to you, is it unaffordable to others, such as local young people? Is there some way of helping to address this?

Some years ago, Nesta Wyn Jones, a North Wales farmer and poet, realised that the increasing number of people moving to the area was eroding the local culture and changing the main language of communication. She started holding language classes where students also learnt about the local culture and customs. Nowadays, many incomers across Wales learn Welsh, and the challenge now is to help them move on from being learners to using the language in their daily lives. Part of this is lifting the blinkers so people realise there is a rich diversity of cultures around them, especially as these are often rooted in the landscape, and often reflect much that people moving to the countryside are keen to create.

As is often the case with permaculture, it all comes back to observation: noticing what is already there, rather than what we want it to look like, or think it ‘should’ look like. But it’s important to remember that observation isn’t only about looking: listening is a big part of it too. Observation means taking time to listen to people who are already there, and who know the land and whose lives and stories are an integral part of the landscape. It means realising that traditional knowledge is not static, that rural communities are not homogenous, and that conventions have developed for a reason, which will, no doubt, change again.

Most of all, observation means being open to learn from people with different perspectives, different experiences, different ways of holding and sharing knowledge. Because more often than not, when you take time to observe, to listen, and to learn about what was there before you (and will perhaps be there long after you’ve gone,) then you find unexpected connections and shared values that prove the sum to be so much greater than the parts.