By Kelda Lorax

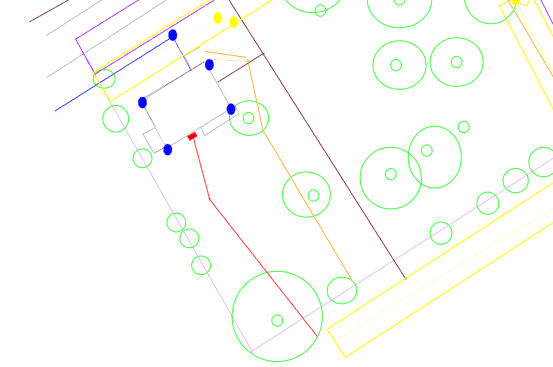

One of the first strategies in making a brilliant permaculture design is to create a base map showing the site’s main components as they are right now. Easy, right?

One would think…, but over the years I’ve come across complications and this article is meant to shed some light on how to clarify a design site’s boundaries. And yes, you want to define your boundaries now rather than get lost in space during the design process.

Some examples of unclear boundaries:

(and right, there’s a whole spin-off Social Permaculture article one can write about this topic too!)

- The whole site is collectively owned by the tribe, intentional community, grandparents, etc, and your part is a small piece of it.

- You have permission to work outside of your own property lines.

- The site is already designed and installed and you’re adding an additional feature, like it’s a home site where you’re adding a food forest.

- You have easements to consider

Boundaries allow you as the designer to focus on understanding what the land wants to be at that one location, unleashes your creative potential, and ideally allows you and your team to manage a beautiful abundant garden (or whatever) into existence. Without boundaries, all of these things become a little, to a lot more, difficult to plan for.

The first step is to acknowledge that you do want boundaries. Of course in an ideal future world your gardens may spill into the whole neighborhood being an abundant oasis, but if you dream so big that you can’t manage your own one piece, the project is more likely to fail. Boundaries allow you to focus on the here and now for absolute success, and building on that success is a task that happens sometime in the future.

Let’s take the above examples piece by piece.

Scenario One: The whole site is collectively owned by the tribe, intentional community, grandparents, etc, and your part is a small piece of it. This is especially tricky (or lovely!) when divisions of land have never been defined by a surveyor and someone says“You know, around your cabin” or “in that forest glade by the creek” or something precious and inexact. Like any community, getting a read of how much land “around your cabin” means can mean some time researching how much land others use, if there are any hard feelings about it, and this is tricky, if certain kinds of uses means more or less land will be accepted as granted to you. (Note: not just granted, but accepted as yours).

Maybe other people use roughly a half-acre, except if they have livestock than it’s larger, and except if they have piles of garbage and everyone wishes they just had 1/20th acre outside they’re back door and no more. Take a subtle read of this, making notes that will also inform other parts of your design (your maintenance strategy, zones, etc).

Another thing to consider is if your design site is going to encompass your center of initiative or if that is elsewhere.

“Center of Initiative” is used in permaculture design to mean the place where your activity emanates from, because the main human(s) is part of the envisioned ecosystem. This can get abstract quickly so consider two different examples: Someone lives in a community house and they’re designing their own private garden outdoor space. Sure, they could sleep there if they want to, but mostly, they cook and sleep and eat all at locations in or adjacent to the community house. On the other hand, someone is designing a site a half-mile walk from a community house that’s used once or twice a week, but most people have private space in which they not just garden, but nap, and cook, and invite friends over, etc. For the first example, the house is still the center of initiative for this design and in the second example, the design site is. The subtle differences allow you to ask clarifying questions not just about space requirements, but storage and access questions, different kinds of needs and yields being met at the design site, etc. In some communities, there is a hybrid of people who live at the community’s center of initiative and those who live in a place that is more their own.

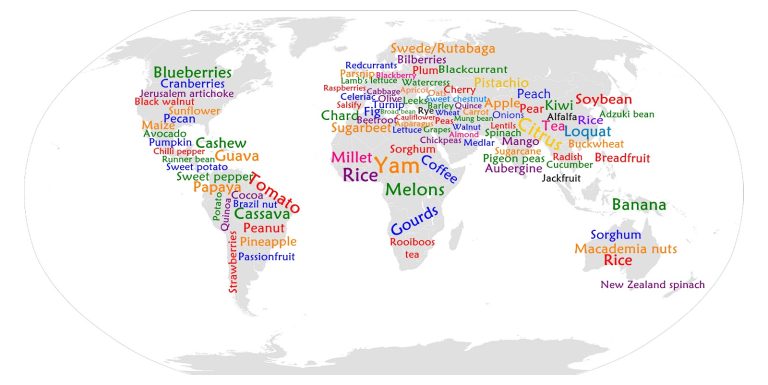

A third thing to consider are the ecological boundaries. If possible, let’s not do square “property” lines when not needed, but base your boundaries on watershed/slope, ecological transition zones, and sensible things like “from the access road to the forest”.

Again, it might be tempting to not have “outside lines” on your base map, especially if you hope that you’ll expand someday. But for now, take it from someone who’s done it many times, put some boundaries on your research or creativity (ie, put those outside lines on your base map!) so your work can deepen into the site and flower, rather than exponentially bounce around to outer-space without a clear what’s what. This doesn’t mean you’ll need a fence, ot that your boundaries mean you can’t expand later, but just give yourself a break with certain parameters for design and not others. On the other hand, if your design site is bigger than you can fully design at the moment, it’s totally fine to mark on area included within your base map as “for later planning”.

Scenario two: You have permission to work outside of your own property lines.

Neat! But simmer down. The biggest mistake I’ve seen with including land not yours on your base map is that the designer is not actually you, but a team. It’s wonderful that your corner site is close to a roundabout that also needs gardens, and you have permission from the neighborhood association to take it over. But you should pause to consider stakeholders, like the other 3 property owners who interact with the site.

If your stakeholders are different than your primary design, than it is a different base map and a different design site. Go ahead and dream about how you now have extra Zone 3 area for your garlic, but don’t assume no one else cares, or be prepared for the consequences. Okay okay, guilty as charged, I have nut trees growing outside my design site on family land, where we checked in with most of the stakeholders but not in a completely “let’s all design together” or even legal way, just enough people didn’t really care. But I also know I can’t harangue my extended family if a crazy uncle wants to install a putt-putt golf course right there. I know I’ll need to talk them into a nut tree overstory and I’m okay with not having control of the outcome.

Scenario three: The site is already designed and installed and you’re adding an additional feature, like if its a home site where you’re adding a food forest. It’s incredibly common for someone to catch the permaculture bug once they’ve already installed with a prior Master Gardener lens or something. There are some pitfalls though in “let’s install a permaculture over there”.

The biggest one is that permaculture isn’t an object, it’s a process. You bet there are kick-ass gardeners who know more about soil and weather and organic management than you do. Good. But if the site has never been looked at from a permaculture lens than some exciting connections might not be happening. In most any situations where you as a designer are invited in, it makes sense to look at the whole site. Whether you are paid to do so, or encouraged to do so or not, is a separate issue to tease out.

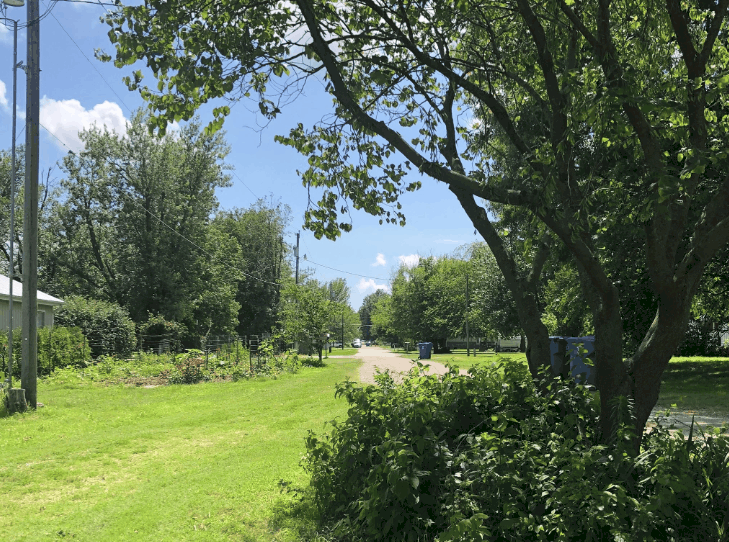

For example, your brother got access to land and says “do a permaculture over there, I’ll pay for materials”. Cool, it’s your opportunity to show off what you learned at liberal art college! He’s looking at you expectantly, or maybe you’re even at the plant nursery together and he’s getting impatient. He doesn’t care about a base map, he just wants some cool plants and a reason to talk to the cute gardener next door. What to do? Don’t. Okay okay, sometimes I’d humor someone by buying a few token plants (they can always be moved later) but permaculture is the DESIGN not the outcome. Your time here is better spent with a cup of ice tea looking at the “garden site” but also watching how everyone moves through the whole site, how sun and water flow, and importantly how the dog chases squirrels back and forth where “the permaculture” is supposed to go, making any future planting there a total waste of time. Only you care about the base map, and it’s only in your head, but do it up right anyway. The client may only care about a small piece, but explaining the process of observation (of everything within the boundaries) is what ultimately helps them build a relationship with the land, even if they don’t hear you the first time. This human-ecosystem relationship-building is often the unspoken job of the permaculture designer anyway.

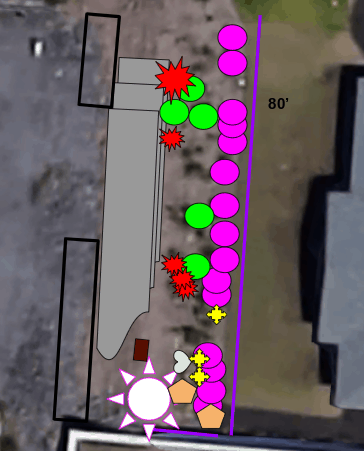

In a somewhat easier situation, the whole site has been designed with permaculture flows and sectors in mind, and an area has been identified as needing its own design and installation. Wonderful! This can be its own base map, with boundaries set similarly to Scenario One, with one important caveat: there should be at least one sketch of how your piece fits into the overall site. Usually this would be part of the Flow or Zone Map, or it could be part of the Seasonal Overlay of gardens, or it could be that this was on the Phase Planning list to address when money was available. Whatever it is, connecting your piece to the larger site needs to be done, at least in your mind. If you’re presenting this design professionally in some sense, your small “design site” needs to be connected to the larger site both in description of the site and placement on a map.

Scenario four: you have easements onto others land, or they use yours.

I can think of only one situation for which to exclude this on the base map, and this is if you use an access road to get to a site, surrounded by land that you don’t manage. Really, your site doesn’t start until you get to your site.

If it’s your land though that others travel through, than designing and anticipating their flow is part of your design.

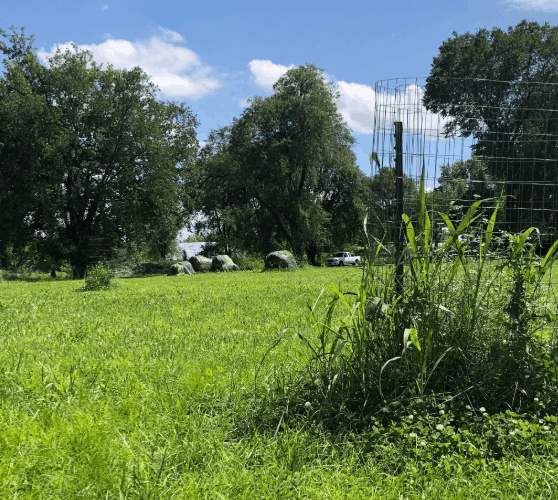

The most common easements are where utility companies have power to enter, and destroy at will. For sure, this is included in your base map, as well as clearances for equipment or whatever destruction may ensue. It’s okay, just plan for it. No expensive fruit trees or fountains, think annual gardens, portable livestock shelters, or even medicinal herbs where the roots are harvested, and let the utility visit do work for you too! Map these areas like any microclimate, with its own set of opportunities and constraints. I tend to plan wide garden pathways over natural gas, sewer, cable lines, etc. Then you know exactly where it is (as far as not digging into it yourself) and if they should ever need servicing, damage to your overall project will be minimal.

I also know of sites where land is available for cheaper because of some major utility running through it. EMF’s aside (and that’s a big aside, a whole topic in itself), yes these are also included on the base map. Please do consider that this land may have been used by wildlife, or even pedestrians, as corridors for movement, and are often rich ecological zones in their own right. Avoid the temptation to make it all feel like your land just because you bought it.

Hopefully you have a clearer understanding of some of the intricacies of what to include and not include in your base map, and where the boundary between your design and other designers meet. Yes, we hope that good planning spills across the boundaries for deep planetary healing, but let’s start one site at at time!