In a forest, the plants collaborate.

They take turns blooming, share space, distribute different nutrients and succeed each other over generations. In our home gardens, we can create diverse, low-maintenance food forests by mimicking these patterns. In its most basic form, this is called companion planting, and gardeners have been doing it for millennia.

You probably know the classic “Three Sisters” example. Native Americans grew corn, beans and squash in a shared space because together they repelled pests and provided a successional yield. I have heard from some old-timers that there was actually a fourth Sister: lupine, a self-seeding, nitrogen-fixing biennial that was planted all around the corn patch to repair the soil.

Ironically, as much as I am a true believer in perennial polyculture gardening, I don’t grow the Sisters. I like to hill my corn (like potatoes) and that disrupts the baby beans and squash. I also find that the corn patch needs more than just the beans (and/or lupine) to repair the soil. So I plant the corn, let it get a few inches high, then plant potatoes in between the stalks. Every week or so, I hill up the dirt around the corn and potatoes with a hoe. I do plant squash, but only on the ends of the rows, so that they can sprawl out away from the patch.

Then, after harvesting corn and potatoes, I cover crop the whole thing with fava beans over the winter to repair and hold the soil for the next rotation.

How to Grow a Permaculture Food Forest

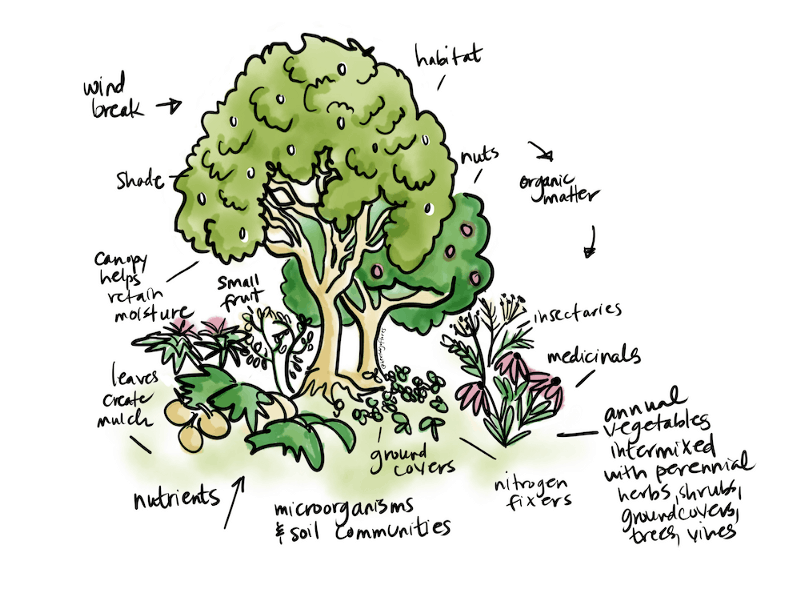

In permaculture, we use food forests to grow as much as possible on a small piece of land. Using those principles, we design garden beds with a collection of complementary perennial trees, shrubs, herbs, ground covers, roots and annual vegetables called “guilds” that are placed in a microclimate landscape best suited for the group. The idea is to group plants together for specific reasons, encourage them to spread into permanent, self-managing landscapes, and thus reduce the amount of effort it takes to grow food.

You don’t have to plant a whole food forest at once. You can carve out niches and build one guild at a time. As they grow, these plantings will attract birds, pollinators, microorganisms and fungi. Over time, as you add more and more guilds, your entire space will yield to nature, becoming your own handcrafted Eden.

How to Build a Guild

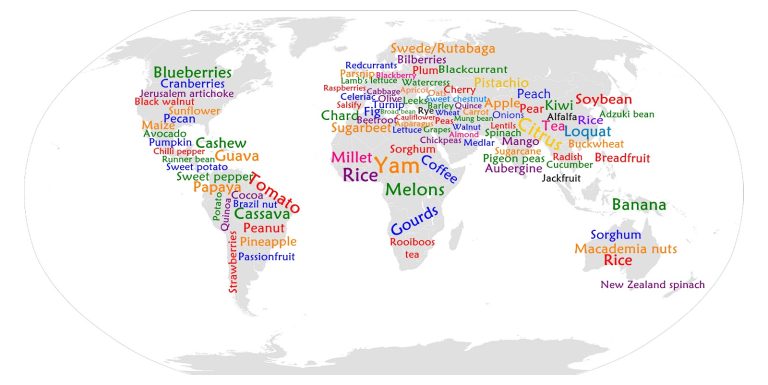

So exactly which plants do we group with which other plants? It takes a lifetime to learn all the differing functions, get familiar with the size of plants at maturity, with their growing patterns and individual needs. There are some great books on the topic, and any search for “companion planting,” “food forests” or “perennial polycultures” will keep you busy reading and designing all winter.

For now, I offer you a handful of my personal favorites from years of experiments with hundreds of plant combinations that yielded mixed results. These are the guilds that I continue to plant in every food forest I design.

Blueberries, strawberries, valerian, yarrow, spinach/lettuce/orach

Blueberries are slow-growing, water-thirsty and thrive in an acidic mulch like sawdust. Strawberries also enjoy the acidic mulch, and can get well established as a ground cover before the mature blueberries shade them out. Valerian and yarrow are clumping, blooming medicinal perennials that attract beneficial insects and help build soil for the berries. Together they look great and share space without much intervention. Sow the spinach between the spaces and alternate with patches of lettuce and orach.

Apples, horseradish, clary sage, kale

Apples cast deep shade and only a handful of plants will thrive under them. Horseradish repels diseases common to apples, and the two are a classic pair. Because I often use it in my apothecary, and because it doesn’t mind a bit of shade, I add clary sage. The fuzzy, aromatic biennial, which grows up to 6 feet tall, glimmers throughout year two with huge plumes of purple flowers. Interplant a few different kinds of kale and you will have a rainbow of foliage.

Figs, seaberry, canna, comfrey, squash

If you have space, this guild is epic in every way: year-round harvest, giant flowers, mulch crops and vegetables. Visually, it’s Jurassic. Figs can get quite large at maturity and tend to sprawl. Between those sprawling shoots you can plant comfrey, which will fill the space with fuzzy foliage and tubular flowers that pollinators love. Seaberry fixes nitrogen and also produces a tart, seedy fruit that can be dried or added fresh to a wide array of dishes. The canna has edible roots (similar to tapioca) and needs a bit more sun, so plant it on the southern edge. Poke in your squashes around the border to give the tendrils room to run.

Peaches, rosemary, marigolds, arugula, zinnias, cucumber

Peaches don’t cast a ton of shade. They tend to be sparse with skinny leaves. This means that companions that wouldn’t do well under other fruit trees will do just fine under a peach. I like the way rosemary looks, especially when joined with annual plantings of marigolds, arugula, zinnias, and other tall, showy annual flowers. Cucumbers do enjoy full sun, but smaller varieties can thrive in mottled shade, and I have grown some beauties as a ground cover in this guild.

Pears, echinacea, beets, poppies

There is something about a pear tree in bloom that always reminds me of the iconic Virgin of Guadalupe image that I grew up with. To me, the way a pear tree holds its blooms looks like an angel. As a sort of tribute to that beauty, I plant echinacea with pears. Echinacea is a clumping perennial with fancy daisy-like coneflowers in purple, green, white and pink. It’s medicinal and beneficial to gardens, with a network of thick roots that help to break up the soil and increase nutrient distribution. Beets fit perfectly in the spaces between, and the foliage is visually splendid in this combination. If you want to make it really beautiful, add some poppies, but keep in mind that poppies are heavy feeders, so you’ll need to compensate the soil.

Generally speaking, as a nitrogen fixer, I habitually sprinkle white subterranean clover seed, both as a cover crop and as a living mulch in beds and paths. It makes an awesome cover, attracts pollinators, and can be easily removed when you decide to plant something new. For best results, mix organic clover seed — coated in bacterial inoculant — with fluffy, finished compost and keep it in a bucket for easy access. If there’s a spot with bare soil, sprinkle the seeded compost around and make sure it gets evenly watered until the clover is established.

Finally, please remember that just because plants in a guild support each other, that doesn’t mean they don’t need your support. You need to weed, prune, mulch and clear. You need to harvest the food, save the seeds and participate in the cycles and seasons. A food forest is an ecosystem, and the gardener should be a part of that. In fact, for the first three years, your newly planted guilds might need some extra attention. Think of the baby plants like little puppies — you have to train them, nurture them, and raise them, but if you do a good job, they will be your best friends for many years to come!