Clear feedback is vital to any project. In this article I’ll show you how to collect feedback.

Exhausted. That’s how I feel when my colleagues provide unconstructive feedback or when they avoid communicating. I experience the same sense of exhaustion when I’m moving so fast I don’t take time for reflection. Setting up pathways for providing clear feedback, renegotiation, and evaluation creates healthy relationships and productivity. Even if you’re the only stakeholder in the project, it’s still imperative to track your progress and manage and tweak your process.

Pathways for reflection and accountability generate efficiency. These paths need to be accessible, practiced and integrated. Whoever uses them needs to trust the flow of information, even if you’re working solo, you need to trust your system. Most of all you need to trust in authenticity.

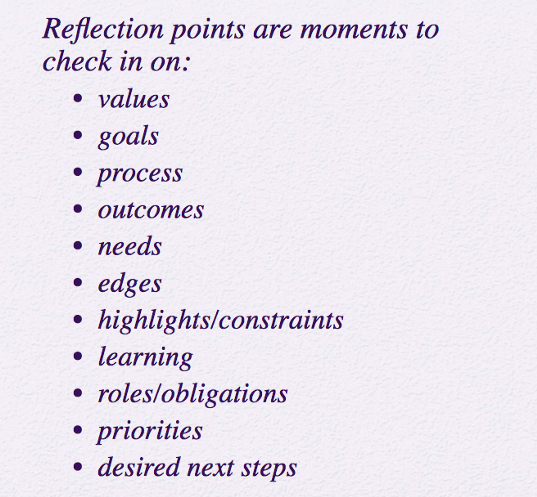

Do you remember what I said about the “Designers Mind” and Emergent Design? I spoke about being intentional and present with your process, and how having a realistic appraisal of the current moment creates authentic connectivity. I shared about how routine reflection and observation keep us linked to the present moment and train us to realize emerging opportunities and limitations. These were data points that I encouraged you to track.

If all of us were actively practicing what we learned about Emergent Design and authentic presence as we collaborated, then we’d be avoiding a lot of burnout, exhaustion, disharmonious relationships and botched designs. Life happens and we are always doing our best. My goal with this section is to share best practices for being a talented tracker. This article provides some tips on how to set up these systems and tools to implement a smoother situation.

If you find yourself at the end of a project or if you’re about to design a new path forward, now is the time to skill up on this art form. It’s not too late to add these valuable layers of reflection and accountability, however designing them into your process from the beginning is far more productive. At this point in the design cycle I encourage you to seek feedback on your project and your presentation.

Feedback

It’s important to set up systems for tracking feedback. When people have active feedback loops designed into a system, they tended to get less worked up and stressed out.

I’ll give you an example. I’m a facilitator. I’ve experienced far too many unproductive meetings where people derail the agenda to try to change the process mid-meeting or because they’ve gone off on some tangent. To solve this, at the beginning of all my meetings, I explain to everyone that there are three designated ways to provide feedback. I tell them that for the time being, we are moving forward with the agenda set by the organizers and that it’s my role to keep everyone on track.

Capture Feedback as it Arises: I explain that there’s a Matters Arising board where anyone can place feedback or tangential ideas that aren’t in the flow of the agenda. The board is visible and available before and after each meeting. Someone from the group reviews the board and takes time to respond to questions, incorporate ideas or feedback and then communicates that to the team before the next meeting. This way the group trusts that the organizers are reviewing comments. If you’re working solo, this might mean having a notebook or journal handy for capturing aha ideas while you’re working, without getting lost in the rabbit hole.

Collect Feedback During Transitions: I consider a transition to be at the end of a meeting or between working groups, or perhaps a new team member exists or enters the scene. Giving people an opportunity to give written feedback during these times is helpful. You can create an online survey, or have people fill out note cards. You could also collect input from a group using a whiteboard. In any case, it’s essential to gather the feedback and let people know the integration process. Then at some point there’s a re-entry of the content and an indication back to the group if feedback was incorporated or not. Perhaps it’s a change in the future agenda. It’s ok to skip incorporating feedback. Being explicit about what is and isn’t integrated helps people gain trust in the process. If you’re working solo this might mean scheduling time to journal between tasks, or at the end of the day.

Provide an Ongoing Portal for Feedback: Sometimes people think of feedback days after an event. So having a place to collect feedback is helpful. Even if the input is only sifted through once a week or once a month, it’s imperative that people trust using the portal.

How to Give Useful Feedback

- Get Consent or Give a Heads Up: Ask for permission. Don’t give solutions or unwanted advice. Pay attention to body language and the person’s reaction to determine if you should continue. If it’s personal say, “Would you be open to me giving you some feedback?” Be sure to pause and let them think. If its professional and you’re their supervisor then give a heads up, “I’d like to give you some feedback.” This example helps the employee prepare. Asking for permission engages the person as a proactive problem solver. Respect their boundaries if they say no. You can keep the door open by saying that they can let you know if they’d like to receive it later.

- Give Feedback in Private: Don’t criticize others in public or in front of another person, unless it was a previous agreement. Understand that people are far more impacted by adverse events and feedback than positive, for example, people are often more worried about losing money than winning the same amount of money.

- Provide Context: Communicate the type of feedback being provided and be explicit about the process for its delivery. Tell the recipient that there will be a designated time for them to reply to all the input if this is applicable. Perhaps even give them time to process their feedback quietly, in writing or with a peer before responding.

- Be Constructive: Use positive and proactive language. Focus on behavior, not personality. Don’t judge. Be specific, clear and concise. Don’t use technical words. Keep the tone of feedback collaborative. Use high vibration words instead of a low vibration.

- Feedback Sandwich: Start and end with positive feedback. It creates intimacy and opens up the reward part of the brain which helps people stay out of their defensive response mechanism. Give critiques in the form of questions, for example, “How do you think that your presentation went?” or “How do you think this x impacted y?” Share gratitude.

- Understand Your Motivation: Be clear about why you are contributing feedback. Can the person do anything about it? Are you sure it isn’t your hang-ups or hurts? Would appreciation or validation work better? What is the logjam, the one essential feedback?

- Diversify Types of Feedback: Mix in positive/appreciations, empathy/connection/how it impacted you or reminded you of a similar experience, recommendations or resources, suggestions for improvement, resonance and agreement, questions or considerations, and encouragement.

- Think Cumulatively: Integrate your feedback with something said earlier in the conversation or a previous meeting. Notice and comment on cumulative improvements or transitions.

On Receiving Feedback

- Honesty: Let someone know if feedback is unwanted or unwarranted. You always have the right to choose to engage with feedback. It’s ok to say, “No, I don’t want to hear your feedback.” or “I’m open to hearing feedback, and this is how and when I’d like you to share.” In some situations choosing to be exempt from receiving feedback could cost you your job or friendship, so you’ll have to navigate this with careful and clear communication.

- Be Open-Minded: Consider feedback as constructive. You get to learn from others. You get to understand others and see a new perspective and likely grow. Listen non-defensively. Don’t interrupt or defend. Don’t take it personally. Stay centered. Say thank you. Decide how you can incorporate the feedback — what are you going to do about it? It’s up to you if you want to take it on board or not.

- Take Your Time: Don’t immediately respond to feedback, ask for a moment to reflect and gather your thoughts and questions. Repeat back what you hear.

- Triangulation: Check to see if others have the same feedback. Ask someone you trust if you’re unclear or confused about receiving or incorporating a specific piece of feedback. If you feel triggered, try combining forgiveness and humor.

Practice Feedback Loops

- Requesting feedback: Ask for feedback to help build relationships and learn.

- Pattern Reflection: Ask yourself what is your experience receiving feedback? How has feedback you’ve given been received? How often do you incorporate feedback? Trial and error is self-collected feedback that is especially useful from a pattern perspective.

- Feedback on Feedback : Ask for reflection on your style of giving and receiving feedback.

When Feedback Turns Into Conflict

- Handling conflict: Be willing to compromise or agree to disagree. Value yourself by knowing your options, needs and wants. Respect the possibilities, needs, and desires of others.

- Be Proactive: Express negative thoughts positively and receive feedback undoubtedly.

- Seek to Relate: Empathic assertion example, “I hear that you are x, and I respect and understand that y, and I also have a need z.”

- Hold Firm to Boundaries if Needed: Escalating assertion example, “If you don’t do x or continue to do y, this is the consequence z.”

Create a Culture of Valuing Feedback

If relating to or anticipating feedback is negative or stressful, it will not likely be productive. Value an open mindset. Know that input and perspective are essential for growth. Understand and discuss with your team, family or friends why feedback is useful. Consider that getting feedback is training offered for free. It’s about actions not you, learn and improve.

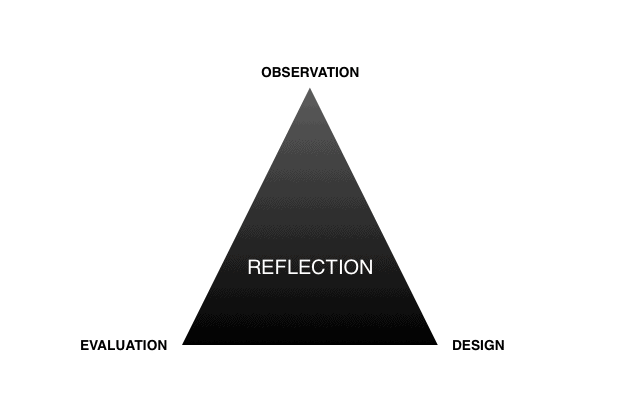

Evaluation

Evaluation is a process of collecting information. It combines smoothly in conjunction with surveying and reflection. Evaluation is unique in that it is precisely about the past. Feedback is also very similar to evaluation in that both gather inputs on process and outcomes of a project or action. Feedback is often considered more specific to matters that arise which are unanticipated. Something bubbles up and needs a container to capture the reflection. Whereas evaluation is a particular process used to collect feedback at predetermined intervals. There’s overlap.

Evaluation is a powerful tool to help us celebrate or get unstuck, assess our outcomes and process, and redesign or tweak our forward momentum. There is often a fear of evaluation because of past traumas where it might have been completed in a judging mindset. Evaluation is not about the success or failure of a project. It’s not about judging the good or bad, or right or wrong way of managing the process. If you set your project up anticipating agility, you know and appreciate that life happens, and things don’t always go as planned. I always say, “it’s not about accomplishing the desired outcomes, it’s more about being present with each decision along the journey.”

I’ll use the analogy of a spider web and a ship. If you consider each strand of the web as a task, what happens to that web when the wind blows? Some of the tasks shift or break. Have you ever noticed how a spider takes the broken parts of their web and re-anchors the section with a new line? With the ship, imagine that the structure is a container for your intentions. However, you can’t control the water or the storms at sea. This is life. The wind blows and changes the direction of our sails or the lines of our network and intentions within the web of our awareness. The evaluation is not about judging any of this as right or wrong. Instead, it’s about taking a clear assessment of what is real and perceived and using that information to make decisions. Successful evaluation is remaining open to ongoing feedback loops and dynamically tweaking the program accordingly.

Evaluation doesn’t need to be about collecting extensive data for scientific accuracy, reliability, and validity. Generalizations and recommendations are okay if that’s what you or your team decide. If you have clients or stakeholders, such as project investors or foundation support, then find out what type of evaluation they require. Don’t make this process over-complicated or collect so much data that the results are burdensome.

Sample Evaluation Process:

This process can be as simple as a single meeting, an afternoon tea, or an entire weekend retreat. It’s up to you to determine how in depth you want to make this evaluation cycle. The most crucial element is that it happens.

- Define the goals, purpose, and scope of the evaluation and feedback loops. What types of information and outcomes do you want to track? How will you monitor and assess them?

- Identify what will happen with the evaluation and feedback processes once they get implemented

- Determine who and what you will evaluate, and how

- Incorporate qualitative (your observations, opinions, and feelings) and quantitative (the facts and figures) measures

- Apply short and long-term assessment of yields/impact

- Revisit the beginning. What did you initially intend to track? For example, what were your original goals and how can you assess progress or achievement?

- Gather all your feedback and evaluation data that came in during previous evaluation periods. Assess and interpret the data you collected.

- Document the outcomes once you finish reflecting and assessing your evaluation data.

- Shift into the renegotiation process if needed.

How often to evaluate:

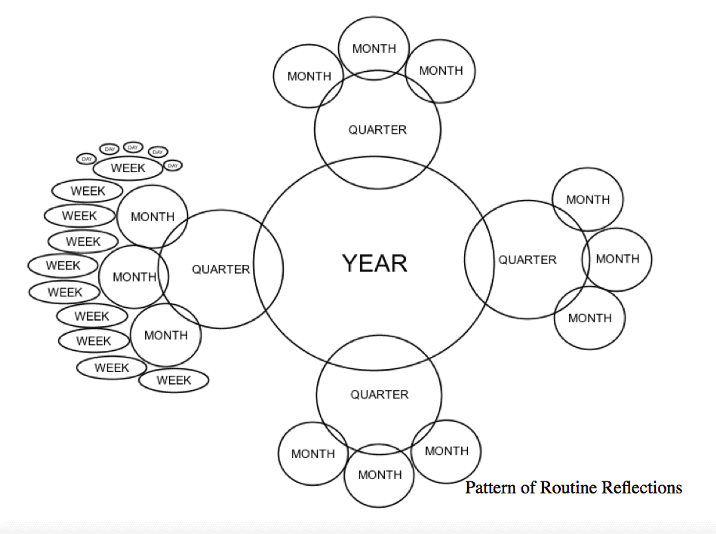

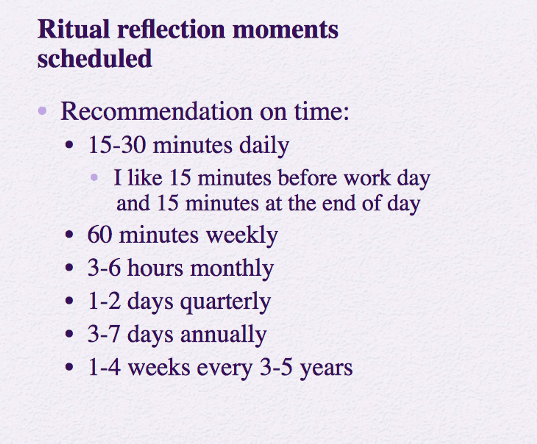

I have upheld this pattern of routine reflection and evaluation for the past fifteen years. Apparently, it works for me as a project manager and designer, or I wouldn’t keep engaging.

Disclaimer: The routine reflection intervals above and timelines below are for extensive ongoing projects. Obviously smaller projects may have an evaluation cycle that only lasts one season or even one day. Gauge the size and duration of your project to how often and how long you’ll engage in the reflection.

Where and When to Direct Attention:

Patterns: On an annual and quarterly basis I focus my routine reflection on evaluation (past) and observations (present) of meta level thinking. I assess the big picture, look for patterns and design (future) fresh goals to move forward. I reflect on my values and long term goals, needs and desired outcomes. I track and assess my qualitative and quantitative data from this pattern level.

Integration: I use monthly hinge points of evaluation to connect the big picture patterns with the details. This moment is where I’m taking that qualitative and quantitative data from what has happened (evaluation) by comparing it to what is happening (observation) or about to happen (design).

Details: On a weekly and daily basis I focus on performing rapid evaluations and reflections that lead me towards making decisions, taking action or renegotiating. I stick to assessing what concrete steps need to happen, my actual accountability (what did I communicate), my real-time capacity to perform (example, am I tired or alert) and the climate of the week or day (the elements that are mostly or entirely out of my control).

The following images provide a summary of how long I might spend in the reflection process, and what I might consider.

Renegotiation

Negotiating is a necessary and everyday part of life. Renegotiating means that for whatever reason we need to adjust and revise a previously arranged intention, design process, promise or agreement. The most critical piece of advice I can offer is always to remember that effective and authentic renegotiations are far more crucial than completion of tasks. Have you ever been in a situation where someone just stops communicating, and you depend on them to complete a step in the project before you can move forward? Would it not be better if they had described the change then just left you hanging? Authentic presence, Accountability and communication are key to renegotiation.

Benefits of renegotiation:

- Eases tension by being more realistic and holistic — predicting and controlling plans creates unnecessary pressure and stress

- Increases overall satisfaction with work

- Allows for more opportunities for making the implicit explicit

- Surfaces where we have conflicts and constraints

- Provides for us to adjust designs to accommodate new opportunities and possibilities

- Creates a sense of agility distributed across time

- Avoids unrealistic desires

- Supports the whole organization or project in evolving

- Establishes a feedback loop and an opportunity for integrating perspectives

- Enables people to be more accountable, which then creates more chance to be realistic in future promise making

- Removes fear of failure from the equation — because the baseline is that everyone’s doing their best

- Processes become more human-centered rather than task-centered (keeps it real)

- Avoids loose threads

Beware — The two most common methods for dealing with falling out of accountability is 1) to just blow off the project or 2) to push yourself beyond reasonable limits to meet the accountability, which is part of predicting and controlling your designs.

These fit into two personality types, those who tend towards avoidance and those towards burnout. The former causes a lot of distrust and disappointment in relationships. The later often adds strain, tension, emotional outbursts or other undesired outcomes. Both perpetuate self-disruptive patterns. That is why it is so crucial that we learn the art of renegotiating with ourselves and others. Efficient renegotiation means that we can handle conflicts and unexpected circumstances with agility, while still making things happen — being proactive and productive.

Another barrier is that negotiation is in the business world known as “getting the better end of a deal,” which means someone else gets less. If you google negotiating or renegotiating the words are most often used to reference business deals, contracts, and the exchange of goods and services. Sometimes renegotiation is also referred to as reneging on a promise or commitment. We often don’t think very highly of people who fail to keep their obligations or responsibilities.

I’d like to change the energy around renegotiation. We need to deconstruct this viewpoint and remember that not only is it possible to renegotiate using integrity with a win-win frame of mind; it is also beneficial to the evolution of the organization or project to encourage the dynamic process. Does this sound familiar? Emergent Design and presence awareness have a lot to do with stepping into the archetype of the dynamic and agile renegotiator.

The need to renegotiate does not imply that the original negotiation was a failure. There are always too many unforeseen factors to consider when making designs. Renegotiating is an ideal response in most instances when a change occurs. Because change is inevitable and I would propose very welcome, organizations and projects would benefit from designing the room for renegotiation. One way of doing this would be to have routine check-ins where team members reflect and report on their progress.

5 Steps Towards Refining Renegotiation

Step 1. Commit to Conscious Engagement

Observe Patterns

- Pay attention to and track how you engage in managing your time and promises.

- The frequency of how often we fall out of accountability and your previous capacity for renegotiation will be critical in determining how you will approach this process, primarily if you’ve developed a negative track record with someone.

Create Effective Solutions

- Changing your language: look into proactive tools like agile management, iterative planning, and dynamic steering as solutions for engaging with project and time management.

- Deal with distress patterns: practice re-evaluation counseling, despair work, non-violent communication and/or other tools for deconstructing and reconditioning your self-limiting and socially conditioned patterns.

- Use systems that work: develop your own ‘Getting Things Done’ approach, which will help you keep better track of your time and accountabilities, and help you be much more realistic and agile.

- Maintain a positive attitude that fosters both respect and courage. Check out Don Miguel Ruiz’s book on Toltec Wisdom: The 4 Agreements.

Step 2. Assessing the Situation

Be Authentic

- Before the renegotiation process can begin, we must admit that we are breaking a promise we’ve made. The breakdown isn’t necessarily anyone’s fault. Focusing on fault finding is counterproductive. Instead, focus on the facts.

Tracking Accountability

- What is the agreement that you made (what were the specifics and conditions, and have there been any modifications)?

- Who is the deal with? What was the design?

- Why and how is the agreement not being met? How has the plan shifted?

- What are/were the effects on other people? Are you aware of the stakeholder’s comfort zone and conditions of satisfaction? Are the design goals being met?

- What are/were the effects on you? What is your comfort zone and terms of achievement?

- Tracking Progress

When you’ve assessed you’re accountabilities and considerations for moving forward, consider these four categories:

A. On Track — There is no need to communicate about any renegotiations.

B. Breakdown/Opportunity — There’s been a breakdown, and your process needs to change, but you will be able to manage and deliver. You’ll need to communicate the change.

C. Breakdown/Opportunity — There’s been a breakdown in the process, and you want to continue, but you’re going to need support. You’ll need to communicate the analysis, the proposal forward, and the explicit request for assistance.

D. Breakdown/Unsure — There’s been a breakdown, and you can no longer deliver the desired outcomes in the projected timeline. You need to renegotiate the project. This may even mean that you design and communicate an exit strategy.

Step 3. Problem Solving

- Be proactive and optimistic

- Determine desired outcomes

- Where’s your comfort and growth zone? It is beneficial to understand what you want and your capacity for flexibility and expansion.

- Know your boundaries. Identifying your goals will help keep you from agreeing to terms that are unacceptable to you.

- Identify plausible solutions

- Make sure it’s SMART: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Timely

Step 4. Managing Promises

Acknowledge the Situation

- To renegotiate a promise efficiently means you acknowledge (ideally before the promise date) that there will be a breakdown in the original commitment, and that you need to renegotiate, with a credible grounding of your new assessment, a new promise.

Good Communication

- Listen and repeat back (paraphrase): Most of the time we are focused on what we are saying, wondering if others heard what we said, or preparing what we want to say next. It’s much more useful to ask probing questions and then listen or even repeat back what you heard.

- Be honest

- Don’t overreact: be nice, use humor and try not to get emotionally involved. Heated emotions are counter-productive. Don’t lose your cool!

Making a Request

- Be clear about what (specifics and conditions), when, why, how and with whom

- Seeking Feedback on Satisfaction (Again, offer or request the following types of satisfaction from your client). Ask your client to be explicit about their needs. Here are examples of explicit communication.

A. Satisfied /No Change: The client is pleased with your work/report, and no change is needed. This is a green light to continue as planned.

B. Satisfied/Change Needed: The client is satisfied. However, they do see room for improvement or a change. Ask them to be very clear in defining the new modification.

C. Unsatisfied / No Change Needed: The client is clear that they are not satisfied with the work, however, due to circumstance (often money, time or attention) they are going to accept how things turned out, and you can carry on with the project.

D. Unsatisfied /Change Needed: Here the client articulates there satisfaction and states a required change, which may include having someone else take over the project.

Step 5. Finding Common Ground

Committed to Renegotiating

- Both parties must be on board

Patterns to Details

- The solution to any renegotiation usually does not lie in the aspects of the transaction. Focusing on the details first will impede the process.

Integrative Decision Making (adapted from Holacracy)

- Present your proposal

- Hold space for everyone to clarify questions or needs

- Create a reaction round, where people can respond with expansive thinking

- Contract: amend and clarify

- Include an objection round: gives an opportunity to solidify language

- Integrate changes and set the final decision

- Design means to track accountability and renegotiate in the future

I hope that this article provided some fresh thinking and tools for producing clear feedback, renegotiation, and evaluation. I think you’ll see enhancement in your relationships and overall productivity when you apply these techniques. The more you use them, the more they will work for you.