What is a perennial vegetable?

Perennial vegetables are plants that live for many years, unlike annual vegetables that need to be replanted yearly. They keep growing and producing food, and can last for decades once established. Growing edible perennials has advantages: you don’t need to replant every year, and once established, they can provide a continuous supply of fresh food for decades. Perennials also tend to be hardy, and can tolerate colder climates and even partial shade.

They don’t replace annual crops but complement them. By adding perennial edibles to your garden guilds, you can increase your year-round yield and enjoy homegrown food and create a more sustainable agriculture overall.

It’s important to note that the term “perennial vegetables” often encompasses plants that are commonly classified as fruits or herbs. However, for the purpose of this article, we are grouping all perennial crops that are edible, but are not trees, together under the umbrella of perennial vegetables.

How much space do you need to grow perennial vegetables?

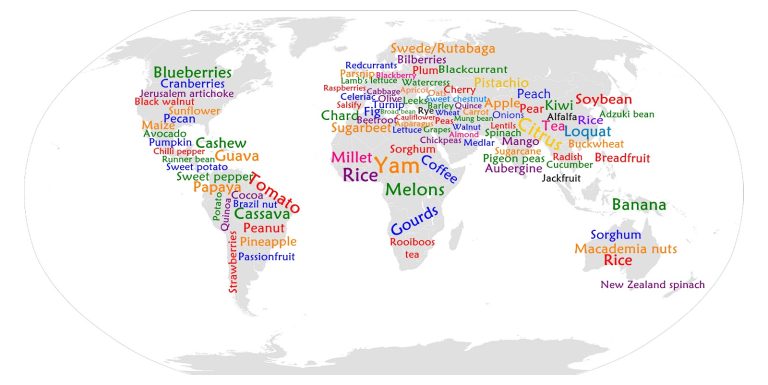

When it comes to growing perennial vegetables, the amount of space you need depends on the specific plants you choose. It’s important to consider the specific needs of each plant as well as your climate and microclimate. Try to start by choosing ones that are suitable for your area, but don’t be afraid to push the boundaries–you might be pleasantly surprised!

The list of edible perennials below includes comments about drought tolerance, cold-hardiness, and light requirements. This information can help you decide which species might be best suited to your particular growing conditions. So, whether you live in a mild climate, a colder region, or somewhere in between, there are likely perennial vegetables that can grow in your area and provide you with nutritious and delicious crops year after year.

If space is limited, don’t worry. Many of the smaller herbs and root vegetables, and even some of the shrubs and vines, can be grown in containers. Just make sure the container is big enough for the plant to grow and mature. The list below also includes information on how much space each plant will need at maturity.

Keep in mind that growing perennials requires patience. Unlike annual vegetables that produce a harvest in just one season, perennials take time to size up and start producing. It may take a year or two before you can enjoy a bountiful harvest, but the long-term benefits are worth it.

Incorporating an edible understory into your existing garden

Chances are, you won’t be planting your edible perennials all by themselves out in the field, right? You’ll be planting them in and around your existing gardens and landscapes, as decoration and as companions for your trees and vegetables. Here are some ways to start slowly transforming your annual vegetable garden into a more perennial one:

Plant Fruit Trees: If you haven’t already, this is top of the list! Consider adding fruit trees like apple, pear, and cherry to your garden. Not only will they provide tasty fruits, but they’ll also create shade and shelter for the understory plants, protecting them from harsh weather conditions.

Start with the Classics: Begin by introducing some well-known species like asparagus, rhubarb, and artichokes. These are hardy and easy to grow, providing a reliable foundation for your edible understory.

Utilize Vertical Space: Grow climbing edibles like grapevines, kiwi, and scarlet runner beans on trellises and arbors. These will not only save space but also add beauty to your garden with their lush foliage and colorful fruits.

Mix in Perennial Herbs: Incorporate perennial herbs such as thyme, oregano, and rosemary among your flowers and shrubs. They not only add flavor to your meals but also attract beneficial insects and pollinators to your garden.

Create a Berry Patch: Set aside an area for growing perennial berries like blueberries, raspberries, and blackberries. They provide delicious fruits season after season and can be a delightful addition to your landscape.

Combine with Ornamentals: Choose ornamental plants with edible parts, such as daylilies (edible flowers), nasturtiums (edible leaves and flowers), and pansies (edible flowers), to enhance the aesthetic appeal of your garden while providing a source of fresh, edible delights.

Create Guilds: Design guilds or companion planting arrangements where different plants support and complement each other. For instance, grow nitrogen-fixing plants like clover or beans alongside heavy feeders like corn or tomatoes to improve soil fertility naturally.

Experiment with Unusual Perennials: Don’t shy away from trying unique edibles like sorrel, lovage, or sea kale. These lesser-known edibles can add diversity and exciting flavors to your dishes.

Establish a Perennial Cover Crop: Integrate perennial cover crops like clover or alfalfa into your garden beds. These plants help maintain soil health, suppress weeds, and attract beneficial insects.

Embrace Succession Planting: Gradually replace some of your annual vegetables with perennial counterparts. For instance, replace annual spinach with perennial New Zealand spinach or swap out traditional basil with perennial basil varieties like African blue basil.

Remember, transforming your garden into a more perennial one takes time and patience. Start small, observe how each plant thrives, and gradually expand your edible understory as you become more familiar with the unique needs and benefits of edible perennials. In doing so, you’ll create a resilient and abundant garden that offers both beauty and sustenance for years to come. Happy gardening!

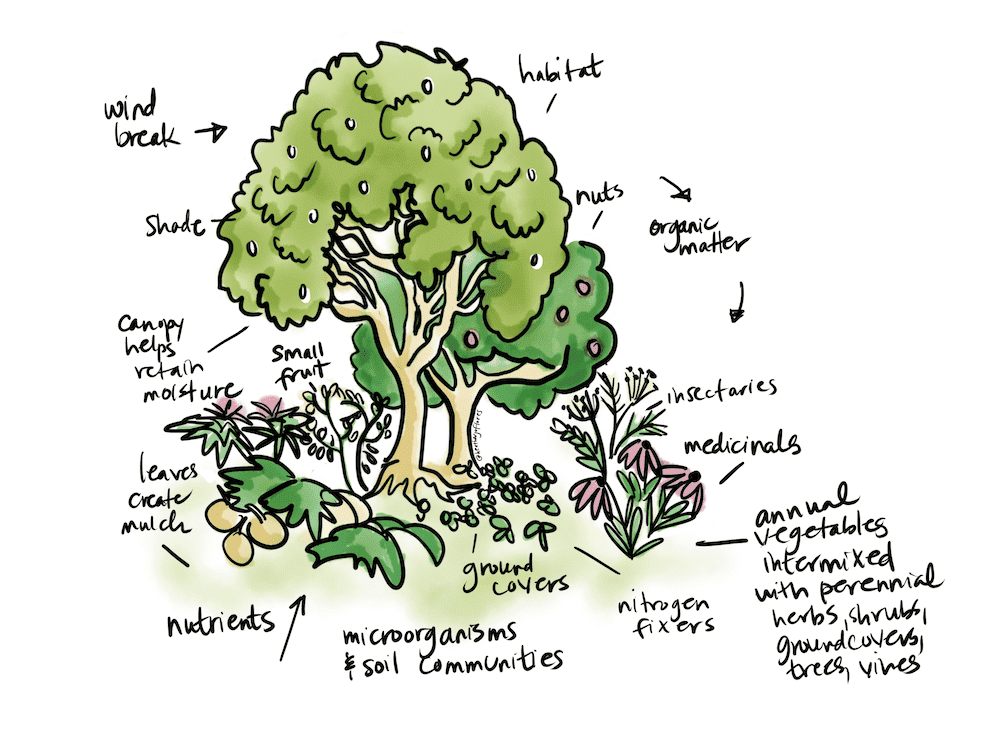

A beginner-friendly review of the food forest gardening approach

All the stuff we are talking about is familiar territory to the experienced permaculture gardener, but just in case you’re not fully versed in the fine art of designing a permaculture food forest, here’s a quick review of how it’s all put together.

Designing a food forest means creating a harmonious, diverse ecosystem that benefits everyone involved, including the plants, the soil, the gardeners, and alll the other species in the the surrounding ecosystem. It’s inspired by the natural structure of forests, where all species thrive together in a balanced environment.

To make a successful food forest, we start by assembling plant communities based on their functions, forms, and lifespans. Think of it like a puzzle, where each plant fits into a specific niche to support others and create a thriving garden that requires low maintenance.

Let’s explore the functions that plants can serve in a food forest:

Edibles: This is the obvious one. Next.

Medicinals and Aromatics: Many plants can be grown for medicine and aromatic purposes.

Ornamentals: There is no such thing as an “ornamental plant.” All plants are food or medicine or both, for somebody. That being said, it’s nice to include a few species just because you think they’re pretty!

Fiber Plants: These build soil and add diversity and can be used for craft projects, like making baskets.

Nitrogen Fixers and Detoxifiers: These help improve the soil by fixing nitrogen or accumulating organic matter for mulch.

Habitat Plants: Create a welcoming environment for wildlife by including habitat species like hawthorn and clover. These can also be placed at the edges of the garden to protect primary crops from hungry critters.

Insectaries: Instead of eliminating all insects, encourage a diverse insect population that can mediate and benefit the garden as a whole. For instance, yarrow and marigold attract beneficial insects that prey on pests.

Now that we have the functions in mind, let’s consider the spatial arrangements of perennial crops in the food forest. Think of a forest and its different layers: roots, ground covers, herbs, shrubs, small trees, tall trees, vines, and water plants. By incorporating all these layers, we maximize space and resources, creating a multidimensional, forest-like environment.

Roots: Some plants are grown for their edible roots. Consider spacing them properly to allow for healthy root development.

Ground Covers: Ground covers protect the soil and can extend to cover large areas to help hold in moisture and nutrients.

Herbs and Vegetables: These plants are perfect for sunny spots and can be grown alongside perennial plants. From kale to calendula, they offer various functions.

Shrubs: Shrubs provide shade and habitat, along with fruits and other products. Consider planting blackberries, lavender, or blueberries.

Small Trees: Small trees produce fruits and nuts and are essential for a lasting food forest. Include apple, pear, and fig trees.

Tall Trees: Tall trees create the forest canopy and offer various resources like wood, fruits, and habitat. Oak, walnut, and chestnut are excellent choices.

Vines: Vines maximize vertical space and can create a jungle-like atmosphere. Consider planting grapevines, kiwi, or passion fruit.

Water Plants: If you have a pond or water system, water plants like lotus and watercress can cleanse the water and provide habitat for wildlife.

Remember that each plant needs enough space to grow healthily. Crowded areas can attract pests and hinder growth, so proper spacing is crucial for the garden’s health and productivity. A food forest design mimics the harmony and productivity of natural forests. By understanding the functions, space, and time each plant requires, we can create a thriving ecosystem that sustains us while benefiting the entire environment.

How the edible understory helps the orchard

In a permaculture system, an orchard can be more than just a collection of fruit trees. By incorporating an edible understory, the orchard can become a self-sustaining and diverse ecosystem. Here’s how the edible understory helps the orchard:

More food in less space: Perennial vegetables, like Egyptian walking onions and Turkish rocket, can grow under the shade of fruit trees, making use of otherwise unused space. They add another layer of productivity to the orchard.

Enhanced ecosystem: The edible understory mimics the diversity found in natural forests. This helps create a balanced and resilient ecosystem that attracts beneficial insects and pollinators, such as bees and butterflies.

Soil improvements: Many perennial vegetables have deep root systems that can help break up compacted soil and bring up nutrients from deeper layers. As the leaves die back each year, they enrich the soil with organic matter, improving its fertility.

Water conservation: The dense foliage of the edible understory helps reduce evaporation and soil moisture loss. This can conserve water and ensure that the fruit trees have a steady water supply even during hot and dry periods.

By incorporating an edible understory into the orchard, we can create a thriving and sustainable food forest. It not only provides a diverse range of edibles but also supports the overall health of the orchard ecosystem.

More than 100 Perennial Vegetables: an A to Z list

Here’s a list of perennial vegetables, organized alphabetically by common name, along with their descriptions, cold-hardiness, drought-tolerance, sunlight requirements, space needs at maturity, and common ways they are eaten.

Akebia (Akebia quinata): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant plant. It prefers full sun to partial shade and requires about 4 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Used in Asian cuisine, where its fruits and young shoots are cooked and added to various dishes. The fruit has a unique flavor, described as a combination of chocolate and vanilla. Hand-pollinate for lots of fruit!

Alpine Strawberries (Fragaria vesca): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Requires 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Berries used fresh, in desserts, and jams.

Abyssinian Kale (Crambe Abyssinica): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and as a cooked green.

Angelica (Angelica archangelica): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers partial shade. Needs 2-3 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in teas and as a flavoring herb.

Apios (Apios americana): A native vine, cold-hardy, and moderately drought-tolerant, needing about 4-6 sq. ft. per plant. Tubers cooked and used in stews and soups.

Artichoke aka Globe Artichoke (Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus): Cold-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 2-3 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Flower buds cooked and used as a vegetable.

Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Requires full sun. Needs 4-6 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Commonly steamed or roasted.

Asparagus Pea (Tetragonolobus purpureus): Cold-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 1 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Pods used in stir-fries and salads.

Bamboo Shoots (Bambusa spp.): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Can tolerate full sun to partial shade. Requires ample space due to its spreading nature. Used in stir-fries and soups.

Babbington’s Leek (Allium ampeloprasum var. babingtonii): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves and bulbs used in various dishes.

Bee Balm (Monarda spp.): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Flowers used in salads and teas.

Bitter Melon (Momordica charantia): Frost-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 2-3 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Fruits used in various Asian dishes.

Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers acidic soil and full sun. Needs 2-4 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Fruits used fresh, in desserts, and jams.

Burdock (Arctium lappa): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Can tolerate partial shade. Requires 2-3 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Young roots cooked or used in stir-fries.

Cape Gooseberry (Physalis peruviana): Cold-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 1 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Fruits used fresh, in desserts, and jams.

Cardoons (Cynara cardunculus): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Stalks cooked and used in Mediterranean dishes.

Celtuce (Lactuca sativa var. asparagina): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Needs 1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Stems used in stir-fries and salads.

Chickweed (Cerastium glomeratum): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers partial shade. Requires 0.5 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and as a garnish. (Many of these leaf vegetables can be sort of tough and heavy, but chickweed is light and sweet.)

Chinese Artichoke (Stachys affinis): Frost-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, needing 1 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Tubers cooked and used in stir-fries.

Chinese Celery (Apium graveolens var. secalinum): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Needs 0.5 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in stir-fries and soups.

Chives (Allium schoenoprasum): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 0.5-1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Used as a garnish or in salads.

Claytonia (Claytonia perfoliata): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Can tolerate partial shade. Requires 0.5 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Used in salads and as a garnish.

Corn Salad (Valerianella spp.): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers partial shade. Requires 0.5 sq. ft. per plant. Used in salads and as a garnish.

Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata): A legume crop, cold-resistant, and moderately drought-tolerant, needing about 1-2 sq. ft. per plant. Young leaves and pods cooked and used in various dishes.

Creeping Jenny (Lysimachia nummularia): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers partial shade. Requires 0.5 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and as a garnish.

Currants (Ribes spp.): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefer full sun but can tolerate partial shade. Needs about 4-6 sq. ft. Used in jams, sauces, and desserts due to their deliciously tangy flavor.

Daylily (Hemerocallis spp.): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Can tolerate partial shade. Needs 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Flowers used in salads and stir-fries.

Egyptian Onion (Allium proliferum): Cold-resistant and easy to grow. Can tolerate partial shade. Needs 0.5-1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Used in stir-fries and soups.

French Sorrel (Rumex scutatus): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Needs 1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Used in salads and cooked as a spinach substitute.

Fuki (Petasites japonicus): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers partial shade. Needs 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Young shoots cooked and used in stir-fries.

Gac Fruit (Momordica cochinchinensis): Cold-sensitive but moderately drought-tolerant, preferring full sunlight. Each vine needs around 9 sq. ft. of space. The ripe fruits are traditionally used in recipes for traditional Vietnamese dishes, soups, and desserts.

Gai Lan (Brassica oleracea var. alboglabra): A leafy green, cold-hardy, and moderately drought-tolerant, requiring 1 sq. ft. per plant. Used in stir-fries and soups.

Garlic Chives (Allium tuberosum): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 0.5-1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Used as a garnish or in stir-fries.

Ginseng (Panax quinquefolius): Cold-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 1 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers partial shade. Roots used in herbal teas and tonics.

Gobo (Arctium lappa): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Can tolerate partial shade. Needs 2-3 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Roots cooked and used in various dishes.

Goji (Lycium barbarum): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Berries eaten fresh, dried, or used in smoothies.

Good King Henry (Blitum bonus-henricus): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant, needing 1 sq. ft. per plant. Cooked as a spinach substitute.

Gooseberry (Ribes spp.): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 2-3 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Fruits used in desserts, jams, and sauces.

Goumi (Eleagnus multiflora): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 4 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Berries used fresh, in desserts, and as a garnish.

Ground Cherry (Physalis heterophylla): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Fruits used fresh, in desserts, and jams.

Groundnut (Apios americana): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 4-6 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Tubers cooked and used in stews.

Hablitzia (Hablitzia tamnoides): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers partial shade. Requires trellising and 2-3 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and stir-fries.

Hamburg Parsley (Petroselinum crispum var. tuberosum): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Needs 1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Roots cooked and used as a vegetable.

Hardy Kiwi (Actinidia arguta): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Requires trellising and 25-40 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Needs male and female plants to fruit. Fruits eaten fresh or used in desserts.

Hoja Santa aka Root Beer Leaf (Piper auritum): Cold-sensitive and prefers moderate moisture. Each plant needs around 4 sq. ft. of space. The leaves are commonly used in recipes for tamales, mole sauces, and stews.

Honeyberry (Lonicera caerulea): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant once established. Blue honeysuckle prefers full to partial sunlight and needs about 3 sq. ft. of space at maturity. The fruits are commonly used in recipes for jams, sauces, and baked goods.

Hops (Humulus lupulus): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Requires ample space due to its vigorous growth. Flowers used in brewing and teas.

Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Needs 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Roots used as a spicy condiment.

Hosta (Hosta spp.): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers partial shade. Needs 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Young shoots cooked and used in stir-fries.

Hyacinth Beans (Lablab purpureus): Frost-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 1-2 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Pods and seeds used in various dishes.

Japanese Ginger (Zingiber mioga): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers partial shade. Needs 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Flower buds used in pickles and stir-fries.

Japanese Wineberry (Rubus phoenicolasius): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Requires trellising and 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Fruits used in desserts and jams.

Kiwi (Actinidia deliciosa): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Requires trellising and 25-40 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Neeeds male and female plants to fruit. Fruits eaten fresh or used in desserts.

Korean Mint (Agastache rugosa): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used for teas and flavoring dishes.

Lovage (Levisticum officinale): Cold-hardy and needing 1-2 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Leaves used as a herb for flavoring soups and stews.

Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum): Frost-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 1-2 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Tubers cooked and used in various dishes.

Mauka (Mirabilis expansa): Frost-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 2-3 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Tubers cooked and used in stews.

Mexican Tarragon (Tagetes lucida): Cold-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 1 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Leaves used as a culinary herb, with a flavor similar to anise.

Mountain Sorrel (Oxyria digyna): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers partial shade. Requires 1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and as a garnish.

Mouse-Ear Chickweed (Cerastium fontanum): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers partial shade. Requires 0.5 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and as a garnish.

Nettles (Urtica dioica): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers partial shade. Requires 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Young leaves cooked and used as a green.

Nodding Onion (Allium cernuum): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 0.5 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Bulbs used in various dishes.

Nopal aka Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia spp.): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 2-3 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Young pads (nopales) cooked and used in various Mexican dishes.

Oca (Oxalis tuberosa): Frost-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 2-3 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Colorful tubers cooked and used in various dishes.

Okinawa Spinach (Gynura crepioides): Frost-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, needing 1 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers partial shade. Leaves used in salads and cooked as a spinach substitute.

Ostrich Fern Fiddleheads (Matteuccia struthiopteris): Cold-resistant and sought after in spring, needing 1 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers partial shade. Young fiddleheads cooked and used in salads and stir-fries.

Orach (Atriplex hortensis): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Requires 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Used in salads and cooked as a spinach substitute.

Pacific Waterleaf (Hydrophyllum tenuipes): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Requires about 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and as a cooked green.

Passionfruit (Passiflora edulis): Cold-sensitive but moderately drought-tolerant, thriving in full sunlight. Each vine needs approximately 12 sq. ft. of space. The ripe fruits are commonly used in recipes for juices, smoothies, desserts, and fruit salads.

Persian Shallot (Allium altissimum): Cold-resistant and needing 1 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Used in cooking as a shallot substitute.

Potherb Mustard (Barbarea vulgaris): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Needs about 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and as a cooked green.

Red Vein Dock (Rumex sanguineus): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Requires about 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and as a cooked green.

Raspberry, blackberry, etc (Rubus spp.): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Fruits used in desserts and jams.

Rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 2-3 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Stalks cooked and used in desserts and jams.

Salad Burnet (Sanguisorba minor): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 0.5 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and as a garnish.

Salsify (Tragopogon porrifolius): A root vegetable with a taste similar to oysters when cooked, cold-resistant, and needing 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Used in stews and as a cooked vegetable.

Satoimo (Colocasia esculenta): Frost-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 1-2 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Corms cooked and used in various Asian dishes.

Sea Asparagus (Salicornia spp.): A succulent, salt-tolerant plant with edible stems, cold-hardy, and drought-tolerant. Needs 0.5-1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Used in salads and as a garnish.

Sea Beet (Beta vulgaris subsp. maritima): Cold-resistant and needing 1 sq. ft. per plant. Used in salads and cooked as a spinach substitute.

Sea Berry (Hippophae rhamnoides): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 4 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Berries used in juices, jams, and desserts.

Sea Kale (Crambe maritima): A coastal plant with tender shoots and leaves, cold-hardy, and moderately drought-tolerant. Requires 2-3 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Used in salads and stir-fries.

Sea Spinach (Spinacia oleracea): A wild edible green, cold-hardy, and moderately drought-tolerant. Needs 0.5 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Used in salads and as a cooked green.

Sea-Milkwort (Glaux maritima): A coastal plant with succulent leaves, cold-hardy, and drought-tolerant. Needs 0.5 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and as a garnish.

Siberian Miner’s Lettuce (Claytonia sibirica): A cold-hardy salad green, requiring 0.5 sq. ft. per plant. Used in salads and as a garnish.

Skirret (Sium sisarum): Frost-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 1 sq. ft. per plant. Used in stews and as a root vegetable.

Sorrel (Rumex acetosa): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Needs 1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Used in salads and cooked as a spinach substitute.

Sticky Chickweed (Stellaria media): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers partial shade. Requires 0.5 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and as a garnish.

Sunchoke aka Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Needs 1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Tubers cooked and used as a root vegetable.

Sweet Cicely (Myrrhis odorata): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Requires 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and as a flavoring herb.

Sweet Potato Leaves (Ipomoea batatas): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Needs 1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and stir-fries.

Taro (Colocasia esculenta): Frost-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 1-2 sq. ft. per plant. Prefers full sun. Corms cooked and used as a root vegetable.

Tarragon (Artemisia dracunculus): Cold-hardy and needing 1 sq. ft. per plant. Leaves used as a culinary herb.

Tree Collards and Tree Kale (Brassica oleracea var. ramosa): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant, needing 1 sq. ft. per plant. Leaves used in salads and as a cooked green.

Valerian (Valeriana officinalis): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers partial shade. Needs 0.5 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Roots used in herbal teas and tinctures.

Vietnamese Mint (Persicaria odorata): Cold-hardy and needing 1 sq. ft. per plant. Leaves used in salads and stir-fries.

Water Celery (Oenanthe javanica): Cold-hardy, aquatic plant needing 1 sq. ft. per plant. Leaves used in soups and stir-fries.

Water Chestnut (Eleocharis dulcis): A cold-hardy, aquatic tuber crop needing 1 sq. ft. per plant. Tubers used in stir-fries and salads.

Wild Leeks (Ramps) (Allium tricoccum): A wild delicacy, cold-resistant, needing 2-4 sq. ft. per plant. Leaves and bulbs used in various dishes.

Yacon (Smallanthus sonchifolius): A root vegetable with a sweet, crisp taste, frost-sensitive but can tolerate some cold, requiring 2-3 sq. ft. per plant. Used fresh and raw in salads or cooked like a sweet potato.

Yam (Dioscorea spp.): A climbing vine with tuberous roots, cold-resistant, and requiring 4-6 sq. ft. per plant. Tubers used in various dishes.

Yarrow (Achillea millefolium): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Needs 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used in salads and teas.

Yucca (Yucca spp.): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Requires ample space due to its size. Young shoots and flowers used in various dishes.

Zapotec Oregano (Lippia graveolens): Cold-hardy and moderately drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Leaves used as a culinary herb.

Zebra Mallow (Malva sylvestris): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Requires 1-2 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Young leaves used in salads and cooked as a green.

Zig Zag Plant (Equisetum hyemale): Cold-hardy and drought-tolerant. Prefers full sun. Needs 1 sq. ft. per plant at maturity. Stems used in various dishes and as a medicinal herb.

These are just some of the many wonderful perennial vegetable species you can incorporate into your edible landscape or garden.

I purposely excluded “tree vegetables”, tree crops, and trees with edible leaves from the above list, and I also didn’t include plants that are technically “annual” but self-seed easily and thus perform like perennials. I just focused on stuff for the understory layer.

Enjoy the diverse and delicious flavors these perennials have to offer. It does take some experimenting in the kitchen to find the sweet spot with actually eating some of these, so don’t get discouraged if your first attempt is Blech! Try preparing it a different way, harvesting at a different time, or curing it differently after harvest. Do your own research!

With this many perennial vegetables to choose from, you’re sure to find some that work for your taste and microclimate. Or create a massive edible perennial sanctuary and try to grow them all! Remember to consider your local climate and growing conditions when choosing which species to include in your perennial vegetable garden.

The Low-Maintenance Garden: Debunking the Myth

Let’s explore the term “low-maintenance garden.” At first glance, it may seem contradictory since gardening inherently involves work. We can’t simply stroll through the garden; we need to tend to it actively. Yet, being in the garden brings numerous rewards. It offers a chance to connect with nature, relax, and find fulfillment. Instead of seeking ways to minimize garden efforts, let’s cherish the joy it brings.

In the wise words of Margaret Atwood, “In the spring, at the end of the day, you should smell like dirt.” Embracing the process of nurturing and cultivating a garden can be deeply fulfilling. It is not merely about reducing work, but rather about creating a space that enriches our lives.

Perennial vegetables indeed reduce the time spent planting new crops annually, but they require attention throughout the year for pruning, mulching, and harvesting. Despite the extra effort, their benefits, like sustainability and nutritious yields, outweigh the work.

Let’s redefine the low-maintenance garden as a space that nurtures our well-being. By devoting time to our gardens, we create a haven of tranquility and sustainability. As we tend to our plants, we also nourish our souls.

As we step into the garden, we not only cultivate the soil but also ourselves. Gardening can be an act of self-care and mindfulness. Let’s celebrate the process of growth and appreciate the harmony it brings to our lives. By nurturing the garden, we become better stewards of the environment and ourselves, cultivating not just plants but also a sense of purpose and fulfillment.

Perennial vegetable pro tips: maintaining the edible understory

Before you run off and plant all 100 of these species in your front-yard food forest, please keep a few things in mind. Maintaining the edible understory of perennial vegetables presents unique challenges and disadvantages, but with these pro tips, you can cultivate a successful and productive garden that complements your annual crops.

Give your perennial vegetables room to grow: A lack of air circulation can be one of the biggest problems in a food forest, and can sometimes be the root cause of aphids, spider mites, slugs, mold, mildew, and many other diseases and infestations. You can put the babies close together then they are small but as soon as they are big enough that the leaves are touching other plants, you’ll either need to move them around to open up space underground for the roots to thrive. Think about the layers of the garden going underground as well, and design your plantings accordingly.

Prune regularly: Removing dead or diseased parts of the plant helps promote healthy growth and prevents the spread of diseases. This ties into the air circulation issue discussed above but also stimulates growth, removes decay, and helps them freshen up for a new season. I know many of us love to envision a completely hands-off “let it wild” garden space, but it’s usually true that pruning, when done correctly and at the right time of year, can make a huge difference in how well a perennial plant grows over the long term. Check out this article for a more in-depth instructions about how to prune shrubs and fruit trees.

Pay attention to soil health: Perennial vegetable gardens thrive in soil rich in organic matter. Regularly adding compost or other organic materials can boost soil fertility. Since perennial vegetables have different soil needs than annuals, understanding the complex interactions between plants, microorganisms, and nutrients in the soil can greatly benefit your garden.

Obtain a yield: Now that you’ve got tons of edible stuff growing–eat it! Go out and harvest all the weird foods, and incorporate them into your diet. Learn when to harvest each plant, which parts to eat, and how to cook them. Some plants may have leaves that taste best when young, while others may produce more interesting flavors as they mature.

Preserve and share the harvest: Drying, canning, pickling, and sharing excess harvest with others are great ways to make the most of your perennial vegetable bounty and build a sense of community. (Pro-Tip: when your perennials start to spread and make babies, host a plant swap! This is a sure-fire way to expand your collection and make friends with the neighbors.)

Where do you buy seeds for perennial vegetables?

When it comes to buying seeds for perennial vegetables, there are a few options available to you. First, you can check out your local nurseries, as they may carry a selection of perennial vegetable seeds. Second, you can explore online seed companies that offer a wide variety of seeds, including perennial vegetables. Lastly, there are specialized organizations that focus specifically on perennial crops, where you can find unique and rare seeds.

If you’re looking to buy seeds online, here are the top 5 places to order perennial vegetable seeds and plants:

One Green World: This website offers a diverse selection of perennial vegetables, plus fruit trees, nut trees, and so much more.

Peace Seedlings: Known for their commitment to preserving heirloom varieties, Peace Seedlings offers a selection of perennial vegetables that are well-suited for different climates.

Real Seeds: If you’re in the UK, Real Seeds is a fantastic option. They have a range of perennial vegetable seeds, including some unusual and exotic varieties.

American Botanical Council: Their book Cornucopia: A Source Book of Edible Plants is a valuable resource for anyone interested in perennial vegetables. It provides detailed information on various edible plants, including their cultivation and uses.

Plants for a Future: This book and website are excellent references for those interested in perennial vegetables. They provide in-depth information on various edible perennials and their culinary uses. However, it’s best to avoid the associated Facebook group, as it’s not actually run by the real PFAF people and can get quite weird.

Where to learn more about food forests, perennial vegetables, and permaculture design.

If you’re interested in learning more about food forests, perennial vegetables, and permaculture design, I have some great resources to recommend! First, let me introduce you to the work of Eric Toensmeier, a renowned expert in perennial vegetables. Eric has written several excellent books, and his knowledge and passion for creating sustainable food systems are truly inspiring.

Now, let’s tie all this information together with the concept of permaculture design. Permaculture is a holistic approach to sustainable living that encompasses food production, energy systems, and more. It focuses on working with nature rather than against it. If you’re interested in learning more about permaculture, check out these free online permaculture courses. In particular, the “Permaculture for Beginners” course is a great place to start your journey.