Different perspectives on the third permaculture ethic

By Karryn Olson

It’s Fall — harvest time in the northern hemisphere — and we are flooded with goodies from our gardens.

As permaculturists, there’s probably no more delightful feeling than nourishing our human Beloveds with the fruit of our humble work caring for the land — because we are in integrity with our People Care and Earth Care ethics. And it’s equally fulfilling to share our extra produce with friends and neighbors… which brings us to….

The third permaculture ethic

When I first learned about permaculture, the third ethic was presented as “Fair Share” — meaning we voluntarily limit our own consumption and reproduction so that we don’t take more than our fair share of resources.

Voluntarily limiting our own reproduction avoids the problematic approach to “population control” that led to policies that often infringe upon the agency of the world’s poor. It also rightfully acknowledges the outsized impacts of the world’s “richer” nations: for example, realigning our lives to reduce our consumption is a great start for people in the U.S., which is home to 5% of the world’s population but generates half the globe’s solid waste and “ranks highest in most consumer categories by a considerable margin, even among industrial nations.”

This focus on the reduction of unsustainable patterns of consumption and impact is a good start, but over the years, I’ve learned of other complimentary, transformative, and visionary versions of this third ethic.

I’ve also been learning and thinking a lot about how one embeds regenerative ethics into the core of our livelihoods, and I have started to see nuanced directives in various versions of the third ethic:

“Future Care” embeds a much longer time horizon into our ethical considerations. It hearkens to the “7th generation principle” codified in the Haudenosaunee Great Law of Peace, which says that every decision must consider the impact of our decisions on the seventh generation to come.

This isn’t just good thinking about natural systems and communities, it’s profoundly smart economic thinking, as it preserves intact and thriving natural capital for future generations. Instead, our current degenerative economic paradigm is eroding our natural capital to the detriment of both current and future generations.

[Heather Jo Flores gives more of the background of Future Care, in her own thoughtful essay about the third ethic. Read it here.]

“Share the Surplus” is useful as a mandate to design our systems so robust that they provide more than we need — so that we can give some of our yield to others — building our local resilience and gift economy. You gift me your extra green beans and I gift you some of my elderberry jam. Yum.

But local economies are about so much more than just circulating stuff — if you are affluent and share with your affluent neighbors, that’s nice; but not addressing the extremes of wealth and poverty. Another side of the same coin is the fact that a drive-by dump of our zucchini burden, or a disconnected drop-off of our extra produce at a food shelter could end up feeling like an un-nourishing replay of the donor/recipient binary.

In this cases, sharing the surplus isn’t transformative.

“Redistribute the Surplus” is a reframe where we endeavor to cultivate mutually beneficial and truly connected friendships with people who might not otherwise have access to the resources which we have in excess. In this way, exchange of surplus happens in both directions, and demonstrates a clear commitment to building Beloved Community.

In this way, these four versions of the third ethic serve as lenses for designing right livelihoods that can have regenerative impact.

I personally think that “redistribute the surplus” is a very potent approach that actually enables us to not only manifest the ethics in our lives and work, but to then magnify our impact by supporting other work that cares for the Earth, Her People, the Future, designs for a surplus, and also addresses the need to redistribute resources.

Here’s an example:

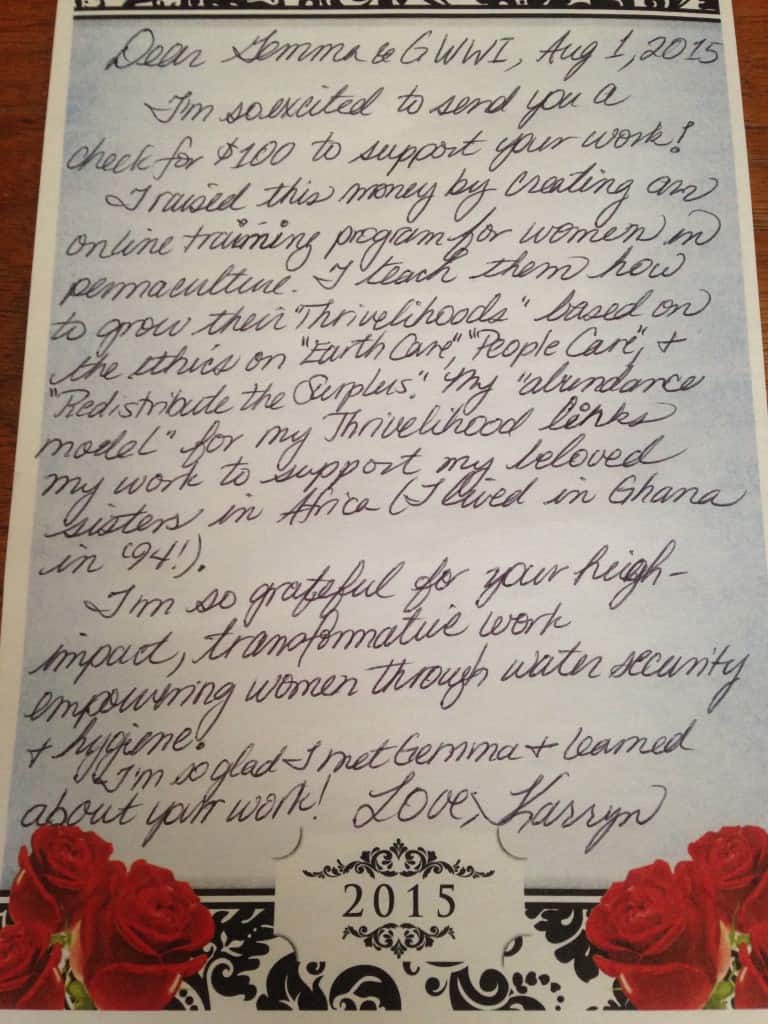

After piloting my first online training program, I sent this letter to the Global Women’s Water Initiative’s “Women and Water Training Programs” which equip grassroots women with the skills and tools for sustainable water solutions — which enable them to tackle the health and violence risks, as well as loss of income and educational opportunities, associated with the lack of safe water and sanitation in their own communities. Now THAT’s a leverage point!

[*Thrivelihoods is a term coined by Jeanine Carlson.]

I met Gemma Bulos, the GWWI Director, at an Advanced Permaculture Training in 2009, and later had the pleasure of hosting her in my home, and she gave an knock-out presentation to my students at Ithaca College. I experienced Gemma’s dedication to women and water, and knew that GWWI was an organization I wanted to support, but at that time our young family didn’t have any extra money to donate.

So, when I created my online trainings (described in the letter above), I linked my success to GWWI, pledging to donate a minimum of 5% of all of my profits to GWWI. Now that gets me out of bed in the morning! Because I know that if I thrive in my work, I can support an organization that I believe is a huge leverage point for women’s empowerment in the face of poverty and climate disruption. I look forward with delight to growing my support of GWWI. You can support GWWI too!

- How do you frame and apply the third ethic?

- How are you Redistributing the Surplus?

- Do you see Redistributing the Surplus as a leverage point?

- How do you decide which organizations to support?

- How do you build and maintain mutually beneficial relationships with these organizations?