What is Lasagna Gardening? How to build a “lazy garden” in 3 easy steps.

Have you ever neglected a garden and found it overrun with weeds the next growing season?

“So much work!” you may initially think.

This article on lasagna gardening aims to show you how in permaculture, we work towards “the most amount of gain for the least amount of work.”

A permaculture garden is essentially, a “lazy garden.”

Why is that?

It’s “lazy” because a lasagna garden allows nature to do the heavy lifting.

Our job is to put the design or thought-work into place so that the natural systems in the soil can most function as efficiently and effectively as possible.

A lasagna garden is merely adding the step of arranging a series of layers that decompose over time and create a fertile garden bed for you instead of you forcing one into existence by roto-tilling. Here’s how to do it in three easy steps.

1. DO NOT TILL.

When we till the soil, we are essentially killing the intricate network of life below the ground upon which the life aboveground depends.

Dr. Elaine Ingham, Founder, President, and Director of Research for Soil Foodweb Inc, says that tilling causes the majority of soil problems. She further states that “use of toxic compounds such as pesticides and inorganic fertilizers which kill the organisms that build structure in the soil.”

A single teaspoon (1 gram) of rich garden soil can hold up to one billion bacteria, several yards of fungal filaments, several thousand protozoa, and scores of nematodes — Kathy Merrifield, retired nematologist at Oregon State University.

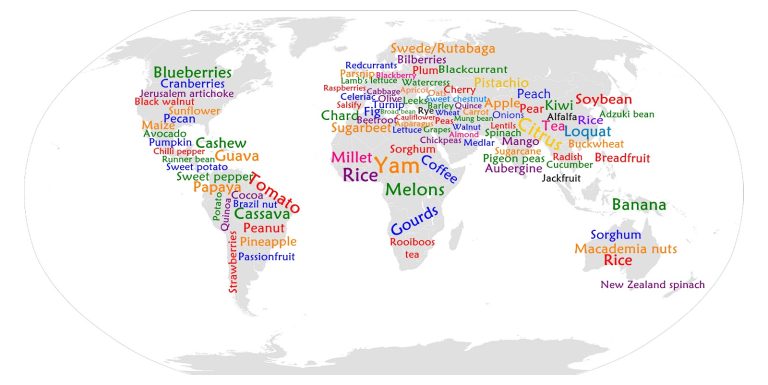

Mycorrhizal fungi (fungi beneficial for plants), also known as the “Internet of the soil,” can be found for miles on end in one contiguous plot of land.

Because this fungus is so extensive and so entrenched in the landscape, it can virtually “field” nutrients to those plants and fellow fungi that need it from one part of your yard that has these nutrients in abundance.

Mycologist Paul Stamets’s book, “Mycelium Running,” is a fascinating read of the secret life of fungi.

The growth of mycelia can be extensive. A form of honey fungus found in the forests of Michigan, which began from a single spore and grows mainly underground, now is estimated to cover 40 acres. The mycelia network is thought to be over 100 tons in weight and is at least 1,500 years old. More recently, another species of fungus discovered in Washington State was found to cover at least 1,500 acres — Encyclopedia.com

What happens when we till?

When we till, we break those fungal connections and killing and churning up the beneficial bacteria and micro-organisms in the soil.

Initially, our soil may have a surge of oxygen, but then without the life to maintain the soil structure, the ecosystem falls apart.

There is a community garden plot in Leesburg, VA, that is a source of great sadness because every year, they till the soil over there and have people start from a blank canvas of lifelessness.

What if my soil is compacted?

If your soil is compacted, use a “broad fork (affiliate link)” or something that aerates the earth, without chopping up the earthworms and fungal strands in the ground.

2. BUILD YOUR LASAGNA GARDEN LAYERS

Here’s one of many possible lasagna garden layers. When creating your lasagna garden, remember the principle,

“Do what you can, with what you have.”

Rather than going out to a store to purchase mulch, for instance, see if you might not have some leaves around your property that simply need to be raked and can use as a lasagna garden “layer.”

A few easy steps to get you lasagna garden started

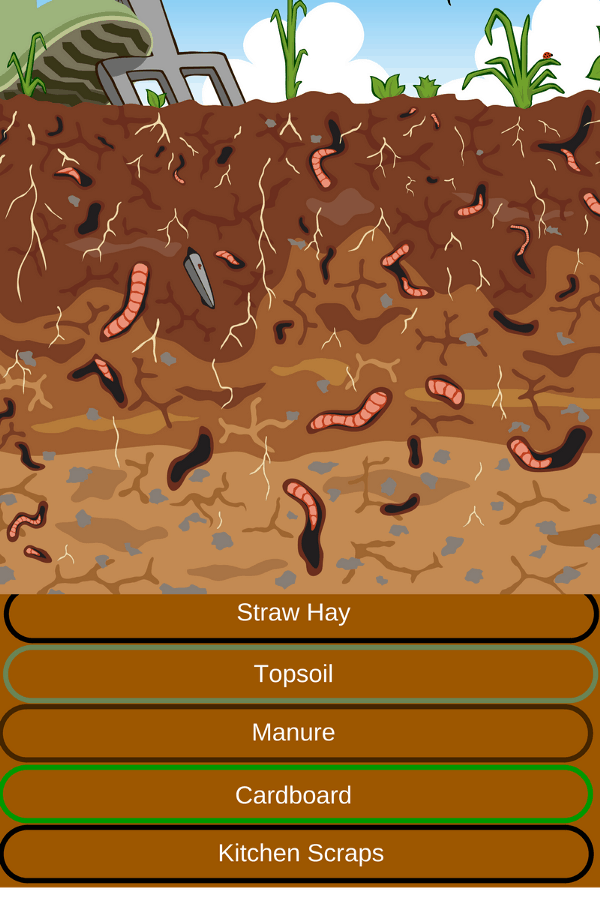

- Bottom Layers

We always start with cardboard at the bottom.

The cardboard acts not only as a weed barrier but somehow mimics the bedrock layer of the soil on the upper crust of the earth.

Lay down the cardboard, overlapping the pieces about 6-inches, to block off the weeds without having to pull them all out. Now you do not need to pull any weeds. Less work for you.

Please note: You will likely still have weeds in your garden even after putting down the cardboard, but they won’t be as aggressive and grow less and less every year as you build up your fertile soil.

In the diagram above, I have put the “kitchen scraps” beneath the cardboard. I do this because I want to make extra sure that no rodents start smelling the scraps from my backyard and dig them up before they have time to decompose.

- Middle Layers

The middle layers can be whatever you have on hand plus the organic compost/soil mix that you initially use to build your garden.

Introduce life in the middle layers. You can add life forms such as nitrogenous bacteria, mycorrhizal fungi, and earthworms to these layers.

- Top Layer

The top of the lasagna garden for us is always a beautiful bed of straw mulch.

Straw mulch works well in the heat and works well in the cold. It eventually disintegrates and becomes part of your soil layers. But initially, when it is newly placed, it helps protect the soil from evaporation and extreme frost. It’s like a blanket!

Dave likes to use scissors and snip the straw mulch up into smaller cuttings so that they don’t stifle the plant growth underneath.

Some of our clients use woodchips instead of straw mulch and have found it to be effective in capturing moisture as well. The only problem with woodchips is that the wood, which is high in carbon, tends to look for nitrogen to use towards its decomposition. If your garden bed is brand new, this could mean losing much-needed nitrogen in the process. And that is why we recommend straw in most gardens.

- Edging

It is always good to define where your garden bed stops and starts. This physical definition is especially true when working with kids who will tend to step into the garden bed even if it raised. Stepping on a garden bed can cause soil compaction and acidification, so we try to minimize that as much as possible.’

When choosing edging, we recommend something that can stand up for a long time, such as brick or cinder blocks.

Cedar is also an excellent wood choice, but it tends to rot after five years and needs replacement. Douglas fir is a cheaper alternative to cedar. Avoid using “pressure-treated” wood, which also happens to be chemically-treated, as well as pressure-treated.

Some of our clients have recommended using a “wall block” to stabilize the corners of their raised square-foot beds and then using wooden planks to build the “walls” of your lasagna garden.

Watch the video below to learn how to build a lasagna garden from scratch using whatever materials you have on hand.

3. PLANT IN YOUR LASAGNA GARDEN

Once you’ve established your lasagna garden, it is reasonable to ask the following questions:

- How soon before I can plant in my lasagna bed?

You can transplant in your garden right away, by poking a hole through the layers, large enough to allow space for your transplant’s roots to spread.

Or you can wait two weeks to have your garden rained on and decompose naturally so that the microbiology in it can establish itself.

- Should I transplant or direct sow into my lasagna garden?

As longtime fans of Grow BioIntensive methods, I recommend starting your plants from seed and transplanting your seedling into the garden once temperatures allow, and the plant has at least “two true leaves.” More on this in a future blog.

However, if you are in the middle of summer or late spring and you would like to catch up with the optimal growing seasons, you can direct sow specific seeds as long as the germinations temperatures are optimal (usually 60–70 F).

- Won’t the straw mulch impede the growth of my plants?

The risk of having straw inhibits my seeds from germinating is yet another reason that I prefer transplanting over direct-sowing. Yes, straw may block light needed for some seeds to germinate. However, if you chop your straw in a very fine way, all you have to do is shift the straw over a bit in the sections in which you direct sow to allow the seed to get direct light and access to the soil.

- I still see weeds growing in my lasagna garden. What did I do wrong?

Nothing. Weeds are often misunderstood plants. Their presence usually indicates that your soil needs remediation of some sort. So when you see them, ask yourself,

- Is that area not yet fertile enough?

- Does it get trampled on a lot?

- Is it compacted or eroded?

In a past article on Building Garden Diversity, you’ll find a list of weeds used for soil remediation.

In permaculture, weeds are considered “pioneering plants” that pave the way for more useful vegetables. As you find them in our gardens, allow yourself to be curious about their presence and purpose. Sometimes you’ll be surprised to see the medicinal uses of plants such as dandelion include healthy digestion, lowering cholesterol, and controlling diabetes.

I do understand that a whole bed of dandelions, however, is not desirable.

So pull your weeds out as soon as you see them and plug in a more desirable plant in its stead. You will find fewer weeds in your first lasagna garden year and fewer still, the following years.

CONCLUSION

Now that you’ve learned three simple steps to build your lasagna garden bed, the challenge is for you to give it a go!

For more information about lasagna gardening and suburban permaculture, check out the “Growing Food in Small Spaces” webinar.