What is Rewilding? Is rewilding a way of off-setting normal life?

By Marit Parker

Rewilding has become a bit of a buzzword recently. It seems to have caught people’s imaginations. However, it might surprise you to learn that, in many rural areas, rewilding can be quite controversial. In this article, I hope to explore why rewilding has become a “thing,” explain why it might be problematic, and who knows? Perhaps I can suggest an alternative way forward.

When people talk about rewilding, they are usually thinking about somewhere remote and far away. But these are not empty spaces. There are already communities here: of plants, animals, and people. However, rewilding projects rarely seem to consider who or what is already there, nor ask what impact the “rewilding” actions will have on existing (often fragile) ecosystems.

Rewilding and biodiversity in the UK

In Britain, upland areas of Wales and Scotland are popular for rewilding, but the sites for rewilding projects often seem to be chosen by people who are unaware of their existing biodiversity. Phrases such as “degraded ecologies” and “green deserts” are used, yet the uplands of Britain contain large areas of blanket bog. These wetland habitats have protected status, because they are home to unique ecosystems.

Blanket bogs consist of peat which can be several feet deep. It acts as a sponge for both rain and carbon. They take thousands of years to form, especially to the depths found on British uplands. This means it is thousands of years since these areas were forested. The names of different aspects of the landscape reflect this, such as Moel Hebog, a mountain in Snowdonia whose name means Bald Hill of the Hawk.

Rewilding projects generally involve planting trees. In this case, “rewilding” means destroying the bog to plant a forest. Nature doesn’t stand still, so reforesting those peat bogs means losing species that have evolved to fill this rare niche.

Before trees can be planted on peat bogs, the bogs have to be drained. This means rainwater is no longer held there. Instead, heavy rainfall rushes straight down into the rivers, often resulting in flooding downstream. This is why there has been severe flooding in the lower reaches of the Severn Valley, for example.

Destruction of peat bogs also releases carbon into the atmosphere. Peat bogs are considered to be the most efficient carbon sink on earth, storing up to 30% of the planet’s carbon despite covering only 3% of the surface.

Reforesting peat bogs also means disturbing the soil. Our knowledge of the soils beneath our feet is limited, but one thing researchers are discovering is that fungi play an important role in soil ecology. Any soil disturbance damages fungi, whose mycelium may stretch for miles. A recent study in Sweden suggests that fungi may be far more important than trees in terms of storing carbon.

It may also come as a surprise to many people to learn that maintaining peat bogs is best done by mixed grazing of native sheep and cattle. Ensuring that this is an economical option for farmers is the simplest way of protecting upland habitats and their capacity for storing water and carbon.

Rewilding and people

Places earmarked for rewilding often have a strong local culture as people depend on each other to survive and make a living in harsh conditions. Their skills, experience and expertise in managing the land may span back generations and this is reflected in the local language or dialect and in the culture, all of which are often deeply intertwined with the climate and terrain. These are resilient communities — yet at the same time they are fragile, because the loss of one or two people can have a big impact on the whole community.

In both Wales and Scotland many feel that rewilding is a continuation of colonialism. There is a long history in both nations of the mountainous landscapes being used as a playground for the rich and for resource extraction, be it slate, water, coal or more recently, renewable energy. Rewilding can be seen as yet another grand idea imposed on the land and on the people with little thought or consideration for local opinions or concerns. Promises of economic benefits through tourism may be greeted with dismay: the lack of affordable housing due to a combination of second homes, holiday cottages and low paid seasonal work means tourism has already resulted in significant rates of homelessness in rural areas, and in the loss of young people to cities.

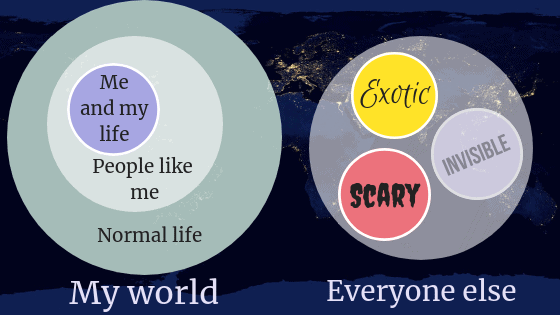

Including local people and their views in discussions about rewilding means thinking not just about other people’s perspectives but also about how we see other people. Much has been written about the “othering” of people who are different from “us”. We tend to see people who are different from us as either scary or exotic, or simply not see them at all.

In rewilding debates, the opinions of local people are often dismissed or simply ignored. The assumption that local knowledge and expertise is irrelevant is familiar within a history of colonisation: the name “Wales” comes from a Saxon word meaning foreigner or barbarian, with connotations of inferiority and “otherness”.

What I find intriguing is how rewilding effectively labels nature as “other”. Some wild things, such as sharks, are scary, and some, such as plankton, are invisible, but rewilding seems to be exciting and exotic.

The problem with this way of seeing the world is that we forget that humans are part of nature. And if humans are part of nature, then where we live and what we make are also part of nature. High rise office blocks may be ugly and power stations are undoubtedly polluting, but they are not in a separate bubble: they are made from and are still part of the earth.

But why does this matter?

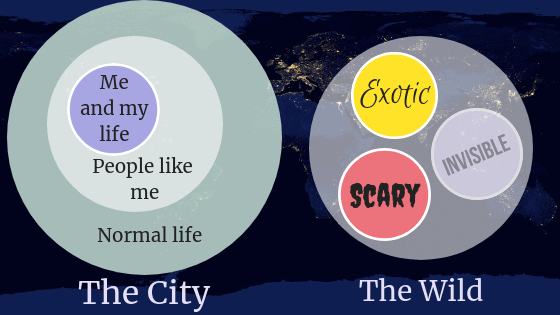

The danger is that labelling certain areas as wild allows unlimited development everywhere else: off-setting nature, instead of carbon. Believing that a place is being restored to its ‘pristine’ wild state means that, in the city, life can carry on as usual.

Is rewilding simply a way of off-setting normal life?

If so, it is not really beneficial; it’s a convenient package that masks the real problem.

Is this why rewilding is popular?

- Is rewilding popular because, if you are living in a manmade cityscape, it helps to know there is somewhere unspoiled out there?

- Is rewilding a thing because, if your days revolve around schedules and shifts, profit margins and targets, you can only stay sane if you know you have made some hillside more “pristine”?

- Is it because, when our plastic, commodified lives get to be too much, it’s good to know there’s a rewilded place we can escape to?

These scenarios suggest that rewilding may actually reinforce the idea that humans are separate from nature and not part of the wild.

Cities feel very different from the countryside but is this because nature is absent, or because we are distracted by other things?

What if, instead of trying to recreate an idealised pre-human landscape, we start seeing cities as habitats and ecosystems in the same way as we see mountains and forests?

Trees are an important part of the cityscape, and each tree supports a whole ecosystem. But glued to smartphones, we forget to notice even our human neighbours, so what chance does a caterpillar or ladybird have, much less a spider? Yet many creatures have evolved to live alongside us in cities and inside our homes.

We can spend days unaware of the sunshine, the rain and the changing seasons, yet the air we breathe, the water we drink, even the sand in the concrete and glass are all part of this earth. A teaspoon of soil can contain more living creatures than the total number of humans alive today. Our own bodies contain even more: we carry whole ecosystems with us on our skin and in our digestive systems wherever we go!

Are we obsessed with rewilding places far away from us because we are so separated from our own natural-ness and wild-ness that we do not see human spaces as places where nature exists?

If humans are as much part of the natural world as every other creature, then human cities are also as much a part of nature as anthills or seabird colonies. What if we look again at how we see cities, and how we see our place within cities?

The Welsh word for habitat is cynefin (pronounced cunn-e-vinn, with a short e as in nest), but it means much more than that: it’s a place you know intimately, a place that you feel safe in. It’s a place you care for and look after because it nurtures you: it’s your home, and the foundation and source of your life.

Rewilding and food

Arguments for rewilding also seem to ignore the whole question of food. Like it or not, cattle and sheep are grown for food. If the hills are cleared for rewilding, what will people eat instead? This is a serious question, because the lowlands are already in use for both arable and livestock farming. While some advocate growing only fruit and vegetables, it’s important to be aware that large scale arable and horticultural farms generally offer far less in terms of biodiversity than permanent pasture. It does puzzle me why upland areas are chosen for rewilding, rather than arable areas where huge fields have been created, and the hedges and shelter belts that used to edge smaller fields have been lost.

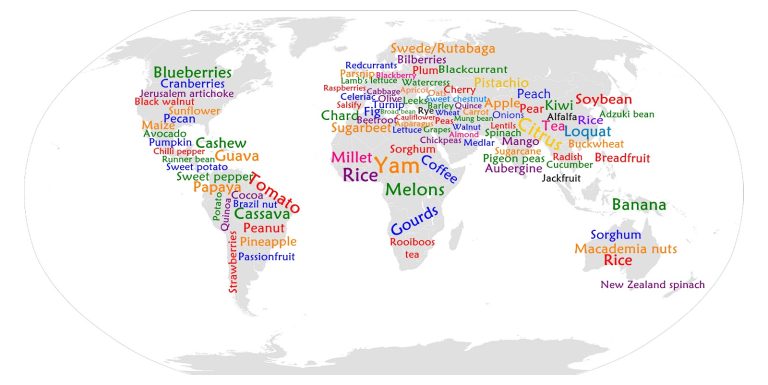

Another factor that needs to be considered is what can be grown, because in the UK’s temperate climate, growing sufficient protein from plants alone is not straightforward. Most vegetarians and vegans rely on imported soya and other pulses, some of which is grown in what was rainforest. Un-wilding one part of the world to re-wild another part makes little sense.

Vandana Shiva says that instead of seeing nature as something wild and separate, we need to see it as essential for life. She suggests that making sure the food we eat is grown in ways that don’t damage nature — or us — is a way of reconnecting with nature. This connection becomes more immediate if we grow some of our food ourselves. This might seem impossible for those living in densely populated areas, but in this free mini-class Becky Ellis suggests a number of ways of finding space to grow things in cities.

Urban rewilding

Instead of convincing ourselves that modern life can be offset by segregating nature and keeping it safe, and at a safe distance, and segregating food-growing so it’s tidied away and unseen, why not ask ourselves what the real difference is between cities and places we think need rewilding?

The main things people notice when they come to the countryside are the quiet, the clean air, and the different pace of life. Instead of trying to preserve parts of the countryside and return them to an arbitrary point in time and evolution, is it not better to tackle the noise and air pollution and the frenetic pace of life in cities?

For example, what would happen if we stopped always looking for new stuff? What would happen if we questioned the endless need for more economic growth, and for profit at any cost? What would happen if we refused to accept work environments with inflexible schedules that erode our well-being, and increase our separation from each other and from the outdoors?

There is a phrase in Welsh, dod at fy nghoed, which means “to reach to a balanced state of mind,” but it translates literally as “to come to my trees,” suggesting that to be well, we need to be connected to the natural world.

Perhaps if we become aware that the wild, the natural world, is all around us, even in towns and cities and on industrial estates, we will start to realise that these are habitats too; that humans and all we do, for good or ill, are part of an integrated, interconnected ecosystem. And perhaps, we will become more connected, or re-connected, to our own wild-ness, our own habitat, our cynefin.

Because perhaps it’s not nature that needs rewilding, but us.